The first thing Nadia Myre did when she went to do her residency on an island in a man-made lake in central France was to make her own charcoal. At a local grocery store on the mainland, she found trimmed willow branches that she eventually built into a little fire when she was back on the island. While serving as a way to create a medium rooted in this place, it was also a way for the Montreal-based Algonquin artist to “to enter my own ideas and personhood into that space,” as she told ARTnews in an interview over Zoom.

Myre used the charcoal to sketch out studies for two photographic prints, After the Fire (2024) and Reduced to a Few Kilos of Ash (2024), that feature in her solo exhibition, “Ropes & Lines” at CIAP Vassivière, the artist residency and exhibition space on Île de Vassivière in France’s Limousin region. After the Fire, depicting a flying bird, was photographed with a “quasi-pinhole” on photographic paper before being scanned and printed. For Reduced to a Few Kilos of Ash, resembling the ruins of a boat hull, Myre scanned the charcoal drawing, then inverted it on her computer before printing it.

As an Algonquin member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, Myre’s first solo show in France is an anti-colonial homecoming of sorts—the French Empire having colonized Quebec for over 200 years before it became a British colony in the 18th century and finally a Canadian province. But Myre said that history didn’t cross her thinking when she preparing for her show. The colonial tensions of Canada, however, are ever-present in her work, especially as an Indigenous person from Montreal, a city cleaved into its anglophone and francophone sections. “The French are slower than the English to awaken to their histories,” Myre said of her experience with colonialism globally.

Another featured work, Still Too Heavy to Carry (2024), consists of dozens of strands of hundreds of handmade ceramic beads that are suspended by a rope-pulley system, rising about eight feet into the air. These cascading beads reference wampum, culturally important beads made by the Indigenous people of the Eastern Woodlands region in North America. The beads Myre uses are various shades of white and off-white, their lack of adornment, she said, relates to the history of how French colonizers made their own wampum to trade with Indigenous people, who didn’t regard these foreign creations with any sense of value.

Though they aren’t part of her own culture, she has adopted them in her art-making as a form of condolence, to honor those who are no longer with us. Because of colonization, Indigenous people aren’t “able to hunt on the land because the animals are sick or to build canoes because the trees are sick,” Myre said, “so there is an epidemic of people killing themselves.”

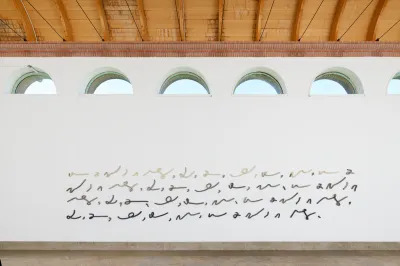

Your Waves of Want Wash Over Us (2024) is another work that takes colonialism head on: a collection of ceramic tubes cast to resemble Gregg shorthand reads “All we want is your trinket, fur, women, land, oil, water.” Myre chose to use shorthand as a way to think about “a universal desire to have an equal language for everyone, a utopic language,” she said, noting that she was “a really atrocious speller when I was younger.” Because Gregg shorthand focuses on recording the sounds a speaker is making, it approaches something more expansive but it too has its shortcomings; basic sounds like “eh” can mean, for example, “yes” to native Algonquin speakers but Creole speakers might interpret it as a sign of one’s not understanding.

Interpreting from a different angle plays a part in [In]tangible Tangles (2021), a series of found images of moccasins from the archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s anthropology department. The series began from pandemic scrolling through various museums’ archives, but these specific images grabbed her attention because the shoes are displayed with their soles facing the camera, instead of at an angle to show as much of the shoe as possible. “You really having this feeling there are bodies in them, like they’re lying down,” Myre said.

In addition to the visible wear and tear on the soles, the shoes are also photographed with tags stating their acquisition number and tribal affiliations. Some were acquired as early as the 1860s, while others are newer, having entered the museum’s holdings only a few decades ago. What the photographs don’t show is under what circumstances they were acquired. Many are shoes for children, reminding Myre of residential schools in both the US and Canada, which separated Indigenous children from their parents in order to assimilate them into the culture of their colonizers and have them forgot their cultural traditions and languages. Often, the children were routinely abused; many were killed there.

These new works build on Myre’s sustained engagement with works that tackle the subject of colonialism, like Indian Act (2000–02), in which people participated in workshops where they beaded over copies of the Indian Act, a piece of Canadian legislation that determines who is Indigenous, or the installation she contributed to CIAP Vassivière’s 2022 group exhibition “Lines of Flight,” featuring a wallpaper that looked at the colonialist exchanges between Indigenous Canadians and the British Empire.

Alexandra McIntosh, CIAP Vassivière’s director, said that this exhibition marks an important moment for the institution and local visitors have an “openness” to discussing such heady topics.

“It was super important to provide an opportunity for an Indigenous artist from North America to address these questions in a very different place, and to also ideally open our perspective on them in the context of Vassivière and France,” McIntosh said.

The Robb Report Gift Guides 2024

EXCLUSIVE: Alexis Mabille Seeks New Investors Amid Financial Restructuring

Black Friday blowout: Massive Apple sale, LG OLED TVs, KitchenAid mixers, Instant Pots, laptops, more

At $750,000 a Throw, Amazon’s NFL Black Friday Ads Are an Easy Score