In 2008, Danish Trinidadian artist Jeannette Ehlers traveled to Ghana, where she visited Fort Prinzenstein, which was built by Danish traders in 1784 and used in the transatlantic slave trade. Located in Keta, in the West African country’s Volta Region, the fort is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site because of its historical significance.

“That was my first encounter with Danish colonial history, and I was shocked to learn about it,” Ehlers recalled, speaking to ARTnews over a video call from her base in Copenhagen.

During the fort tour, she came across a proverb written on a wall in its dungeon: “Until the lion has their historian, the hunter will always be a hero.” “It’s such a powerful proverb,” she said. “I was also puzzled by it. It [had] been on my mind for a long time and I decided subconsciously that I must be one of the historians for the lion.”

Since then, Ehlers has used the proverb in her practice, making it a significant feature in pieces including We’re Magic. We’re Real #3 (These Walls), which she performed alongside Eve Tagny and Sophia Gaspard in September as part of the opening of “Black Ancient Futures” at the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) in Lisbon. During the hour-long performance, the artists tied their braids—some 65 feet of hair in total—to the museum’s facade. The piece alluded to the link between African diasporic identity; the nearby ocean, which enslaved Africans once crossed centuries ago; and Portugal’s industrialization and colonial history.

As the artists walked back and forth during the performance, they said the referenced proverb in Danish, Spanish, Portuguese, and other languages, and moved their braids across the floor. The sound of waves crashing could be heard all the while. According to Ehlers, the performance is about “who is telling the story and what is being told.” That work and We’re Magic. We’re Real #2, a 2020 installation composed of synthetic hair that spins freely in the exhibition space, along with emergency blankets that address the extraction of resources from the Global South by Western countries and colonialism, will be on view until the end of the exhibition on March 17, 2025.

In addition to Ehlers, “Black Ancient Futures” features celebrated artists such as Kiluanji Kia Henda, Jota Mombaça, Evan Ifekoya, and Sandra Mujinga. These artists have appeared regularly in museum exhibitions and biennials, but “Black Ancient Futures” is different from those shows. Curated by João Pinharanda and Camila Maissune, it sets aside false ideas about what art from Africa and its diaspora should look like, and doesn’t assert any one aesthetic. Moreover, its explicit focus on colonialism makes it unusual for a mainstream museum show in Portugal, a country where art about that topic can be considered taboo.

But most works in the show do not portray the violence of colonialism outright. Lungiswa Gqunta’s Sleep in Witness (2024), a site-specific installation made of wire, rocks, and clay, speaks to that sensibility. The work is made up of wire, rocks and clay, with a black and white image of women in the background. The South African artist invites Black women to step onto the clay ground, which she envisions as a place that already existed, to honor those who lived during those times.

“I always chose Black women to help me shape this work by momentarily living in it with me. This landscape is a recognition of the work we do and is my form of continued celebration of our refusal and power,” Gqunta said. “We have shaped many worlds and will continue to do so. Here’s to fierce hoping, deep defiance, and endless collective healing.”

And My Body Carried All of You (2024), by Sandra Mujinga, an Oslo-based artist born in Democratic Republic of Congo, is also among the exhibition’s standouts. Originally commissioned for Japan’s Yokohama Triennale, the piece consists of three sculptures made of steel and fabrics. She thinks of the fabric as skins and the steel part as a skeleton, possibly one that once belonged to an animal.

“I’m quite drawn to thinking about fossils and dinosaurs as a way to speculate on bodies from the past,” the artist said. “And when I am speculating on bodies from the past, it’s very much about perhaps acknowledging that not everyone has access to one’s history. And history in itself is also written from a position of power.”

Mujinga said that the MAAT exhibition is “more of a start,” providing an opportunity to “to be more, to dig deeper” in moving beyond “projections and expectations unto Black bodies.”

As Maissune, the only Black curator at MAAT, put it, this exhibition serves as a “counter narrative,” providing a different perspective to the notion that the Portuguese were “good colonialists,” compared to, say, the British and Belgian. According to Maissune, many think of the Portuguese having been explorers. In fact, Portugal began its colonization of foreign lands in 1418, when the country’s emissaries landed at the island of Porto Santo, off the coast of West Africa. In the centuries afterward, Portugal would go on to enslave more than 5 million Africans.

Mujinga pointed out that Portugal’s colonialist ventures were even copied by other Western countries. Portugal created “blueprints and models that were adapted [and] used in [the] colonization” of countries around the world, she said.

MAAT’s location is itself symbolic within the context of this show. Sited on the banks of the Tangus River, the museum exists not far from the Atlantic Ocean, which was used as a passageway for the ships that brought enslaved Africans to Portugal, aiding in its industrialization and providing this nation with riches.

But the show—and its location—are just one part of a larger discussion that needs to be had in Portugal. Mujinga said conversations about Portugal’s role in colonialism remain “quite fragile and avoided.” And when colonialism is spoken about, it is often presented in “heroic [narratives] rather than also the violence that is rooted in it or the models that were created within that.”

While institutions are acknowledging and having these “difficult conversations,” there needs to be more of those talks, she added. “And for it to be explored more, I think it should also be messier—and also [talked about] outside museums.”

Nadia Myre Brings an Exhibition on French Colonization in Canada to France’s Heartland

Recent Exhibitions at US Museums Explore the Complexity of Puerto Rican Identity

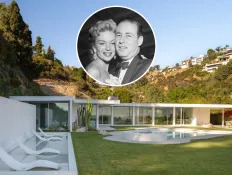

This Revamped $11 Million L.A. Home Dates Back to Hollywood’s Golden Age

Amazon’s Black Friday Sale Includes Can’t-Miss Deals on These Trending Beauty Gifts

ECOVACS has the biggest robot vacuum sale of Black Friday and Cyber Monday

At $750,000 a Throw, Amazon’s NFL Black Friday Ads Are an Easy Score