Few movements in art history have had as lasting a legacy as Surrealism, which utterly transformed our manner of thinking and seeing. In its time, it garnered a remarkable degree of public recognition, and its influence on artists continues to be felt today.

This year marks the centennial of the birth of Surrealism with the publication of the Surrealist Manifesto in October 1924. Actually, make that manifestos, plural, as two tracts appearing within weeks of each other vied for the title. The first was written by Yvan Goll (1891–1950), a French-German poet with close ties to the German Expressionists; the other, more famous treatise was penned by André Breton (1896–1966), a French poet and critic whose talent for tireless self-promotion contributed to his ascension as Surrealism’s de facto leader and ideological enforcer.

Neither Goll nor Breton mentioned art in their respective statements. Moreover, neither actually coined the term Surrealism. That distinction belongs to Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), a poet and prime proponent of the Parisian avant-garde, who used it in a 1917 letter to the Belgian critic Paul Dermée to describe the experimental ballet Parade (1917).

-

What Was Surrealism?

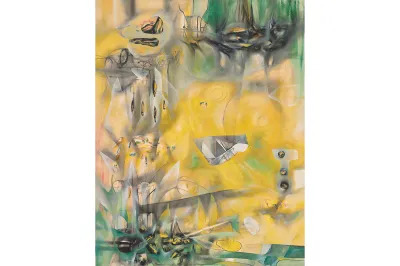

Image Credit: Collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Digital Image copyright © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris Breton defined Surrealism as a way to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” He recast it as an artistic enterprise with his 1928 publication Surrealism and Painting. By then, artists such as Jean Arp, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, René Magritte, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy had been drawn into his orbit.

Stylistically, Surrealism ranged from the quasi-abstraction of Miró to Magritte’s deadpan realism. Originally centered in Paris, it became global in scope, spilling over to the Americas and Asia. Reacting to the carnage of World War I, the movement attacked rationalism and social decorum, upending longstanding artistic precepts and subverting conventional sexual mores with misogynistic élan. Even so, Surrealism attracted a significant cohort of female artists, among them Meret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning, Claude Cahun, and Leonora Carrington.

The Surrealists reveled in a discontinuity best summarized by a line from the 1868 novel Les Chants de Maldoror, which described a “chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table.” This idea became Surrealism’s credo, codified by the collaborative genre known as the cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse). Resembling a game of telephone, but played with drawings, cadavre exquis involved passing a piece of paper around a group of artists. Each would render part of a figure, then hide it by folding the sheet over. Other participants would follow suit, and the result when revealed was predictably disjointed.

-

Surrealism, Freud, and Automatism

Image Credit: Collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Digital Image © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Surrealism was deeply indebted to Sigmund Freud. His belief that the mind could be unlocked through psychoanalytical methods such as the interpretation of dreams made a huge impact on Breton, who’d attended medical school and developed an interest in mental illness before he became a writer. Serving in the French army’s medical corps on the Western Front in World War I, Breton was stationed at a ward in Nantes that treated soldiers for shell shock (what we would today call PTSD), where he applied Freud’s theories while caring for patients.

Breton believed the subconscious could unshackle art from its conventions through automatism, a process that surrendered deliberation to an unimpeded flow of imagination. He described it as a “pure state by which one proposes to express . . . the actual functioning of thought . . . in the absence of any control exercised by reason.” Here again he was indebted to Freud, who pioneered “free association,” which encouraged patients to relay feelings, memories, and reveries in an unregulated rush of words.

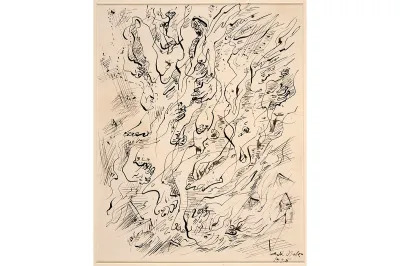

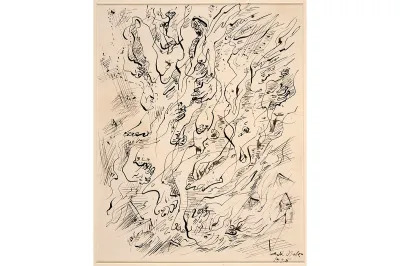

André Masson (1896–1987) developed the artistic application of this method with a series of drawings begun in 1924, characterized by agglomerations of lines produced in a fugue state. Automatism would eventually become foundational to Abstract Expressionism in the post–World War II era.

-

Proto-Surrealism

Image Credit: Collection of the Museo del Prado, Madrid. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. While we think of Surrealism as a 20th-century phenomenon, its roots in art reach much farther back. For much of European art history, depictions of heaven and hell were a constant theme, and in this respect, portrayals of otherworldly planes intersecting our own were an accepted fact of pictorial organization.

Medieval and Renaissance Art

All such art was arguably surreal in this sense, but there were instances of what could be called proto-Surrealism, particularly in the work of Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516), a Dutch/Netherlandish painter whose phantasmagoric compositions are among the most canonical in Western art. Paintings like The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) were much admired by the Surrealists for their bizarre scenery and chaotic juxtaposition of disparate images.

The fanciful portraits of the Italian Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526–93) were also proto-Surrealist, combining still life and trompe l’oeil to cobble imaginary sitters out of objects related to them (a librarian made of books, a cook fashioned out of victuals, and so on).

Circle of Giuseppe Arcimboldo (b. ca. 1527–1593), Anthropomorphic Still Life with Pots, Pans, Cutlery, a Loom, and Tools. Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Romanticism

Surrealism could be considered a backlash to large historical forces—the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution—that developed in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries. The former held that religion and faith must relinquish themselves to the power of reason, effectively severing a connection between the physical and metaphysical that Surrealism would later try to repair.

Surrealism rejected Enlightenment beliefs, but it wasn’t the first movement to do so. In the early 19th century, Romanticism swept across the Continent, its proponents arguing that relying on reason alone shortchanged individual agency by ignoring sensation, both good and bad. Among the artists within its ranks were three—William Blake, Henry Fuseli, and Francisco Goya—whose work could be considered proto-Surrealistic.

A poet as well as an artist, Blake (1757–1827) conjured ecstatic visions of figures set against stars and planetary orbs, radiating coronas of cosmic light that metaphorically burst the straitjacket of logic. Blake critiqued reason in hand-colored engravings like Newton (1795), which depicts the eponymous titan of science seated naked on a rock, bending over a scroll with compass in hand, so fixated on his calculations that he’s blind to everything else.

Fuseli (1741–1825) was a Swiss artist whose crepuscular masterpiece, The Nightmare (1781), plumbed the erotic depths of dreams a century before Freud. It pictures a woman in a diaphanous gown lying prostrate on a bed as a satanic incubus sits on her chest. On the left, a blind horse pokes its head through a curtain. The sexual overtones of The Nightmare are as disturbing as they are unmistakable; the same overtones suffuse Fuseli’s other works, including studies of women whose tinge of fetishistic obsession presaged the same within Surrealism.

One of the iconic names in Western art, Goya (1746–1828) channeled the benighted conditions of late 18th– and early 19th-century Spain as it lay in the smothering grip of the Catholic Church. In 1799 he published The Caprices, a folio of aquatints depicting Spain’s crippling backwardness as a series of stark tableaux populated by hideous dwarfs, cadaverous hags, witches, and other abominations. The signature image of the collection shows a man, head down on a table, beset by scores of bats, cats, and owls. Its caption, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” speaks to the limits of the Enlightenment project to reform behavior.

John Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. John Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Symbolism

In the late 19th century, another group of artists likewise anticipated Surrealism. Calling themselves Symbolists, they explored aspects of the human condition as dreamlike allegories.

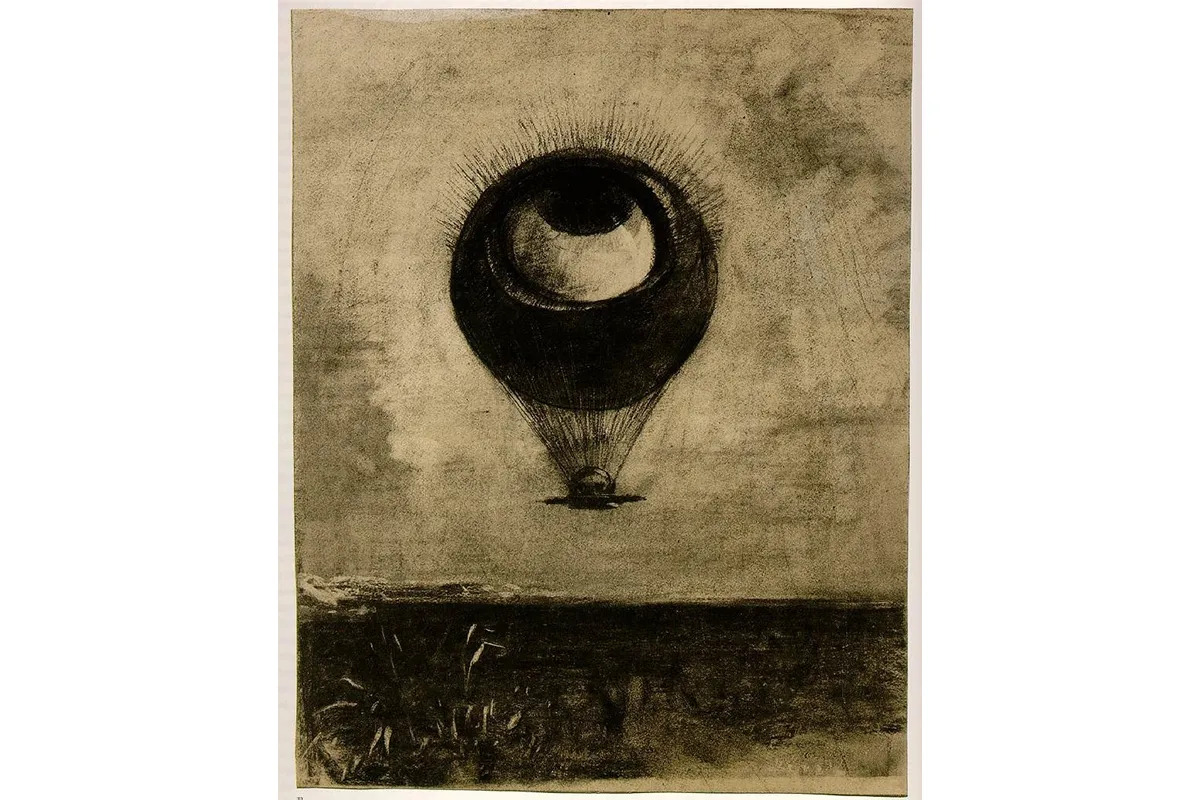

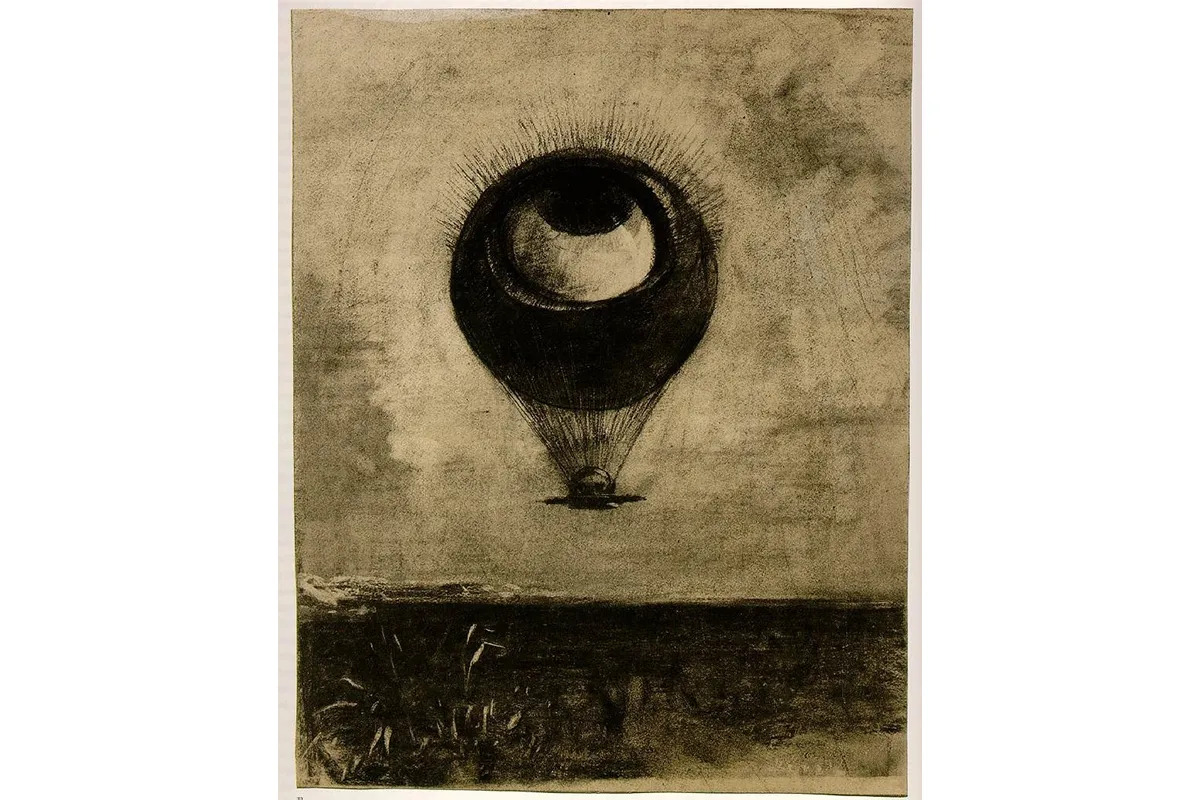

Odilon Redon (1840–1916) is probably the most widely recognized Symbolist thanks to his “noirs,” a series of lithographs and charcoals begun in the 1880s. Among the most extraordinary was The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity (1882). Much of Redon’s work was inspired by writers like Edgar Allan Poe, to whom this rendering of an eyeball ascending the sky was dedicated.

The work of Gustave Moreau (1826–98) was equally hallucinatory, suffusing scenes from Greek mythology and the Bible with a lysergic air of exoticism. His most famous canvas, The Apparition (1874–76), transforms the New Testament tale of John the Baptist’s head being delivered on a platter to Salome into a deliriously decadent apparition of his severed pate floating in front of the barely clothed recipient.

Odilon Redon, Eye-Balloon, 1878. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Post-Impressionism

While Symbolism functioned as a unique chapter in art, it was also the result of the Post-Impressionist context in which it developed. Marquee names of the period—Paul Gaugin, Edvard Munch, and Vincent van Gogh—crossed over into Symbolism.

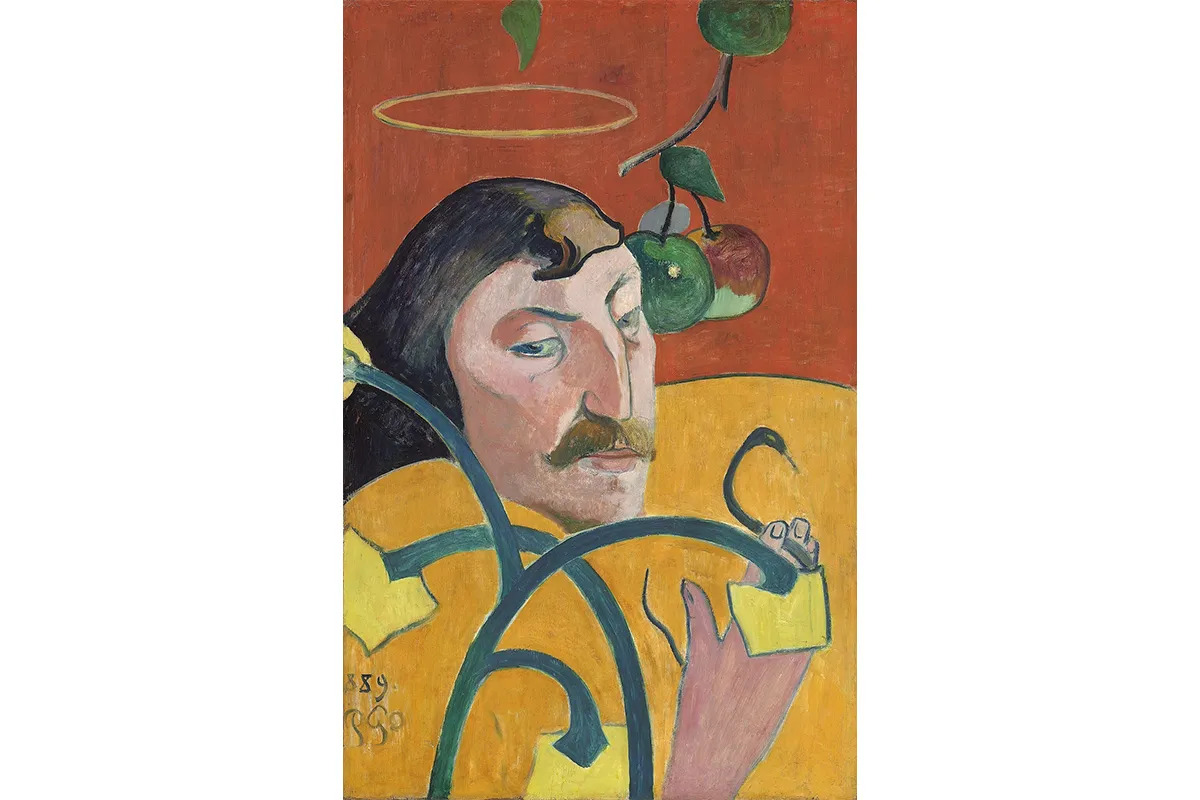

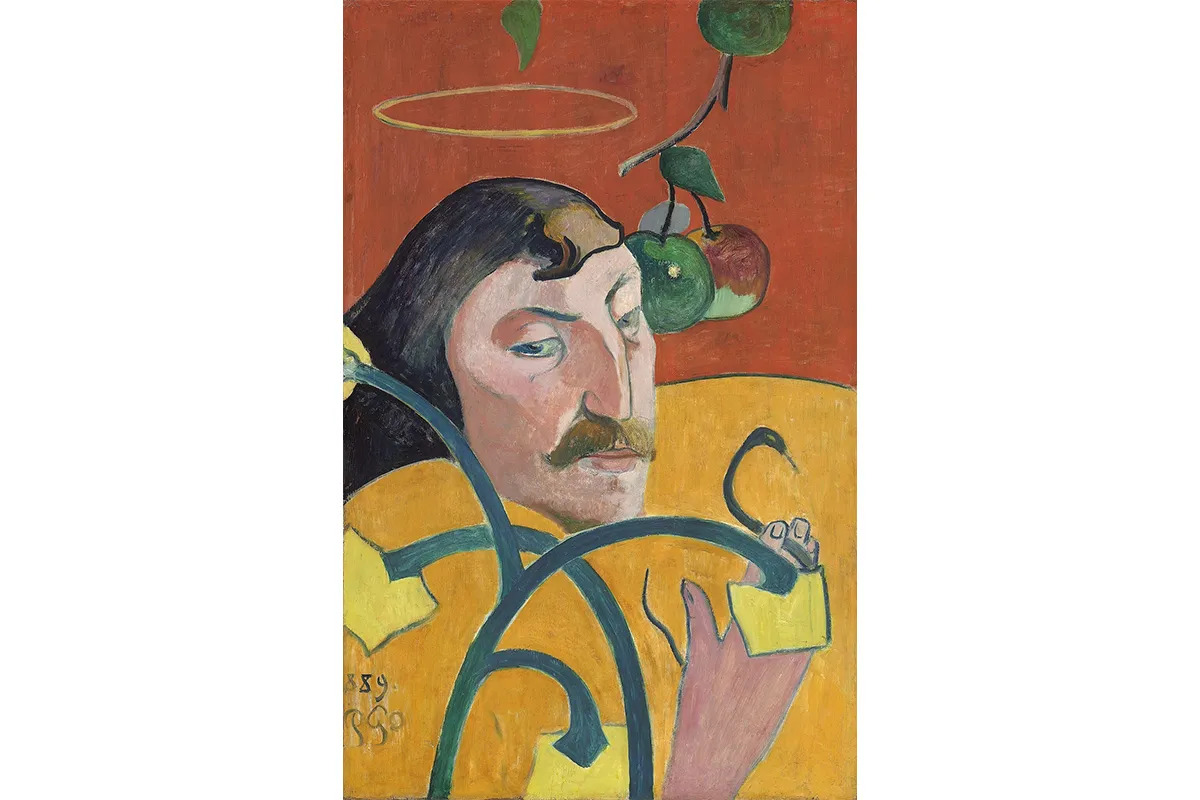

This was especially true of Gaugin, whose Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake (1889) leavened a meditation on good versus evil with a generous dollop of self-regard, and Munch, whose combination of Symbolism and Expressionism resulted in that veritable logo for angst, The Scream (1893). Van Gogh, meanwhile, psychologically supercharged his landscapes and genre scenes, employing frenetic brushwork as a kind of borderline automatism.

Paul Gaugin, Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake, 1889. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. James Ensor

A contemporary of the artists above, James Ensor (1860–1949) also foreshadowed Surrealism. Ensor spent much of his life in Ostend, a resort on the Flanders coast. His family ran a gift emporium there catering to tourists, and it was especially busy during the city’s annual carnival, when the shop sold masks to revelers. These items featured prominently in Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1889), which transplants the Gospel tale of Jesus’s triumphal arrival into Jerusalem to the Belgian capital of Ensor’s day. Jesus is seen in a parade led by a boisterous crowd wearing grotesque masks. Even more uncanny were paintings like Skeletons Warming Themselves (1889), of a group of costumed skeletons gathered around a stove.

James Ensor, Skeletons Warming Themselves, 1889. Collection of the Kimball Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. Photo: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection of the Kimball Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. Photo: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Giorgio de Chirico

While Freud provided the theoretical foundation for Surrealism, Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978) supplied its visual template, arguably exercising an even greater influence than Freud on the Surrealists. His work predated Dada by several years, with paintings like The Enigma of the Oracle going as far back as 1910. He dubbed his approach pittura metafisica (metaphysical art).

A typical de Chirico composition centered on a desolate Italian piazza bounded by colonnades, towers, and other elements of classical architecture, though factories appeared occasionally in the background. His scenes were for the most part devoid of people, populated instead by an odd assortment of objects that included Greco-Roman statuary, mannequins, and cryptic geometrical solids. He used sharp contrasts between light and dark, and long, menacing shadows loomed throughout. His sharply titling perspective led the eye into a kind of spatial purgatory, a trope adopted later by Tanguy, Dalí, and others.

De Chirico’s work was enthusiastically embraced by Breton, who credited it with “preserving for eternity the memory of the true modern mythology.” However, Breton’s view of de Chirico cooled considerably after 1928, by which time the latter had abandoned metaphysical art, turning instead to an odd, and often clunky, blend of classical and baroque motifs.

De Chirico’s most famous paintings spoke to the anxieties of the Industrial Age by evoking a curdled nostalgia for the certainties of antiquity. To this extent, they always expressed the artist’s skepticism toward modernity, a gimlet view that would blossom in his later retardataire style. Still, metaphysical art was ambiguous enough to earn an essential spot within the avant-garde.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Anxiety of Waiting, 1914. Collection of the Fondazione Magnani Rocca, Corte di Mamiano, Italy. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Collection of the Fondazione Magnani Rocca, Corte di Mamiano, Italy. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. -

Dada and Surrealism

Image Credit: Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Surrealism initially began as a breakaway faction of the Dada movement, precipitated by arcane philosophical disputes between Breton and the Dadaist provocateur Tristan Tzara (1896–1963). Nonetheless, both Dadaism and Surrealism grew out of the same horrified reaction to the butchery of WW1 and the same contempt for capitalism and bourgeois propriety.

Dada originated when a group of writers and poets—Tzara, Emmy Hennings, Hugo Ball, and Marcel Janco—came together in Zurich during the winter of 1915, by which time the Western Front had descended into a stalemate. The group assembled at a local club called the Cabaret Voltaire for evenings of nonsensical recitals and other performative acts. To them, absurdism seemed the only sane response to a Europe gone mad. Dada soon established itself in other cities including Berlin, Cologne, and New York. Several artists from these centers—Max Ernst and Jean Arp from Germany, Man Ray from America—would join Breton’s Surrealist camp.

Tzara was key to Dada’s expansion to Paris, where he moved in 1919 to join the staff of Littérature, a magazine edited by Breton; not surprisingly, its pages became a forum for the arguments between them. Their disagreement revolved around the efficacy of art and culture in the aftermath of world-shattering events. Tzara took a nihilistic view that averred the pointlessness of aesthetics. Rejecting Tzara’s anti-art outlook, Breton believed that a new kind of order—Surrealism—could reconstruct a society unraveled by war.

Things came to a head in 1921 with a mock trial presided over by Breton. Ostensibly the defendant was critic Maurice Barrès, a French anarchist turned right-wing apologist for whom Tzara served as a friendly witness. As the proceedings went on, the indictment against Barrès was redirected toward Dada itself, signaling its end as an artistic force.

-

The Rise of Surrealism

Image Credit: Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Photo: John Wronn. Whatever else it was, Surrealism was very much a product of the interwar years, which are now often considered a lull within the same global conflagration. The liminal state of a Continent suspended between peace and war was reflected by the gap between reality and dream that Surrealism mined in the 1920s and ’30s. During these years, Surrealism went from being a marginal idea to becoming a popular-culture fixture of the era. Two exhibitions charted this evolution.

On November 13, 1925, the Exposition Surréaliste, the first-ever survey of Surrealist art, opened at Galerie Pierre Colle in Paris, featuring Arp, Klee, Man Ray, Ernst, Miró, de Chirico, Masson, and Pierre Roy, as well as Pablo Picasso, who’d incongruously submitted one of his Cubist paintings. (Picasso’s inclusion was due to Breton’s acute desire to ally the world’s most famous modern artist to the Surrealist cause.) Though these artists had all previously shown their work, the exhibition marked their debut under Breton’s banner.

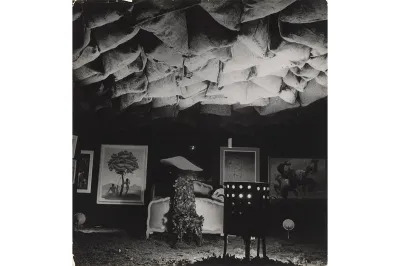

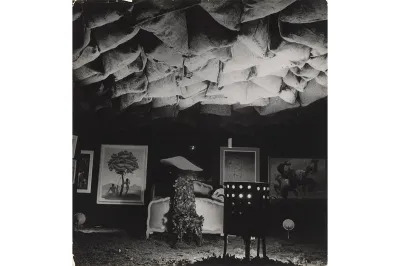

While the 1925 show brought together the core Surrealist group, the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme of 1938 went farther afield. Co-curated by Breton and the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, with Marcel Duchamp, Dalí, and Ernst serving as advisers, the exhibit opened on January 17 at Georges Wildenstein’s Galérie Beaux-Arts in Paris with nearly 300 works by 60 contributors from 14 countries.

Man Ray designed the exhibit’s lighting while the Austrian-Mexican artist and writer Wolfgang Paalen (1905–59) supervised an entryway installation composed of foliage and the Dalí centerpiece Rainy Taxi, an ivy-covered car with a mannequin seated inside under spraying water. Though he never joined the Surrealists officially, Duchamp created the final room, for which he hung hundreds of coal bags stuffed with newspapers from the ceiling.

During the evening opening, the lights went out, forcing attendees to view the show with flashlights. In terms of scale and participants involved, the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme demonstrated the movement’s arrival as a cultural phenomenon.

-

Who Were the Surrealists?

Image Credit: Collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Digital Image copyright © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, 2024. The number of artists identifying themselves as Surrealists grew remarkably in the 1920s and ’30s and included such far-flung practitioners as Tokyo-based Koga Harue, who painted meditations on the industrialization—and militarization—of Japan. But several individuals were mainly responsible for setting the various directions Surrealism would take.

Max Ernst

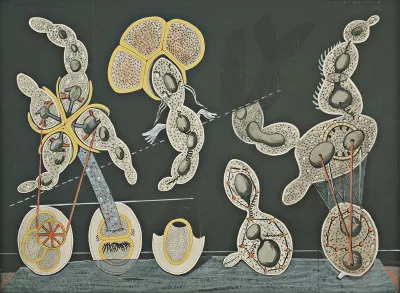

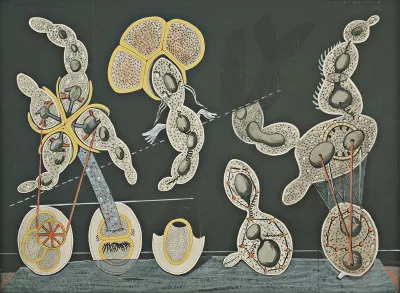

The artist whose work best encapsulated the shift from Dada to Surrealism was Max Ernst (1891–1976), who was born near Cologne. In 1914 he was drafted into the German army, and the trauma he suffered during the war became the defining experience of his art. Based in Cologne during the early 1920s, Ernst fashioned collages out of found illustrations that he overpainted by hand. One example involved a biology-class chart depicting plant cells undergoing mitosis. Turning it upside down, Ernst added a black backdrop and other elements that transformed these cells into circus performers on a tightrope.

Works such as this were consistent with the anarchistic spirit of Dada, but in 1923 Ernst moved in a more enigmatic direction, turning from collage to painting with the impenetrable seaside vista Woman, Old Man, and Flower (1923–24). Begun in Cologne, it was later modified in Paris with the addition of the mysterious, fan-headed woman dominating the composition once Ernst joined the Surrealists there.

Ernst developed techniques that transferred serendipitous, collagelike textures to his work by rubbing or scouring paper or still-wet canvas placed over pieces of wood, window screen, or string. He also laid glass sheets over freshly applied oils, then pulled them up to produce chance surface alterations. Both practices figured prominently in his wartime masterpiece, Europe After the Rain II (1940–42), which imagined the Continent as a blasted postapocalyptic landscape.

Max Ernst, The Forest, 1927. Collection of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Photo: Tel Aviv Museum of Art/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Collection of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Photo: Tel Aviv Museum of Art/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. René Magritte

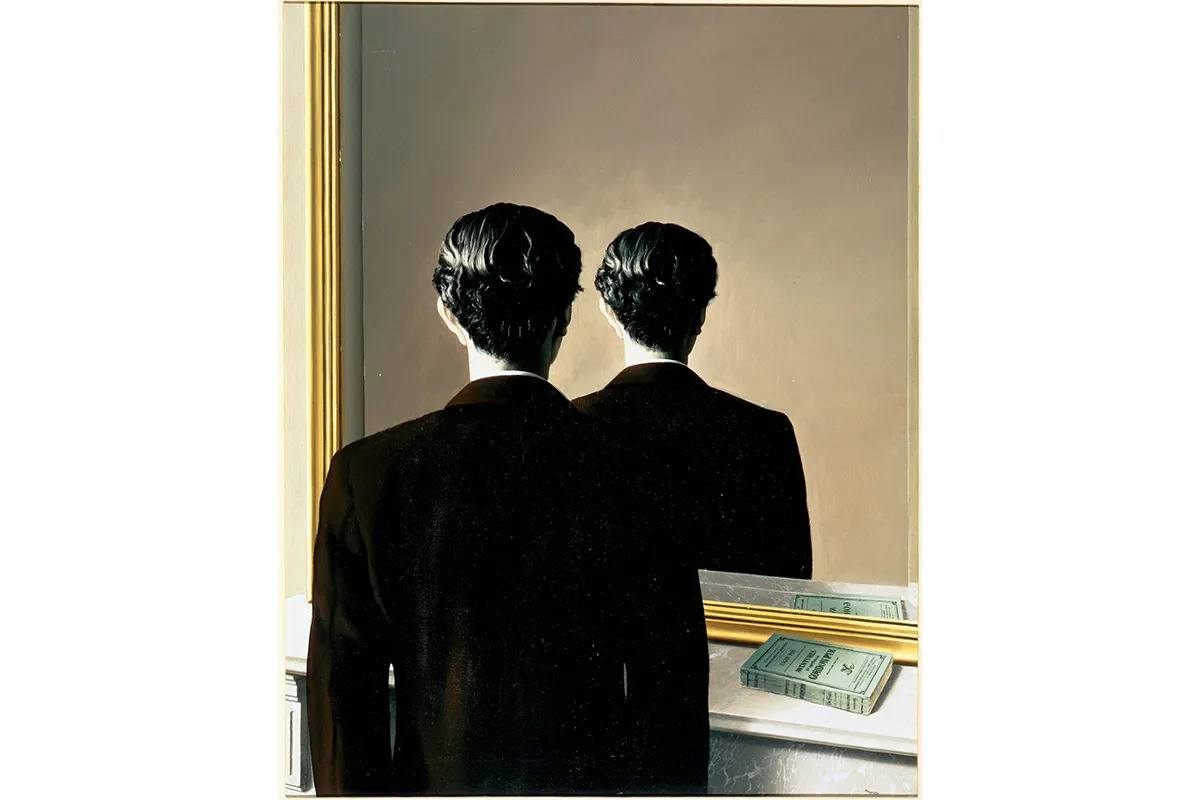

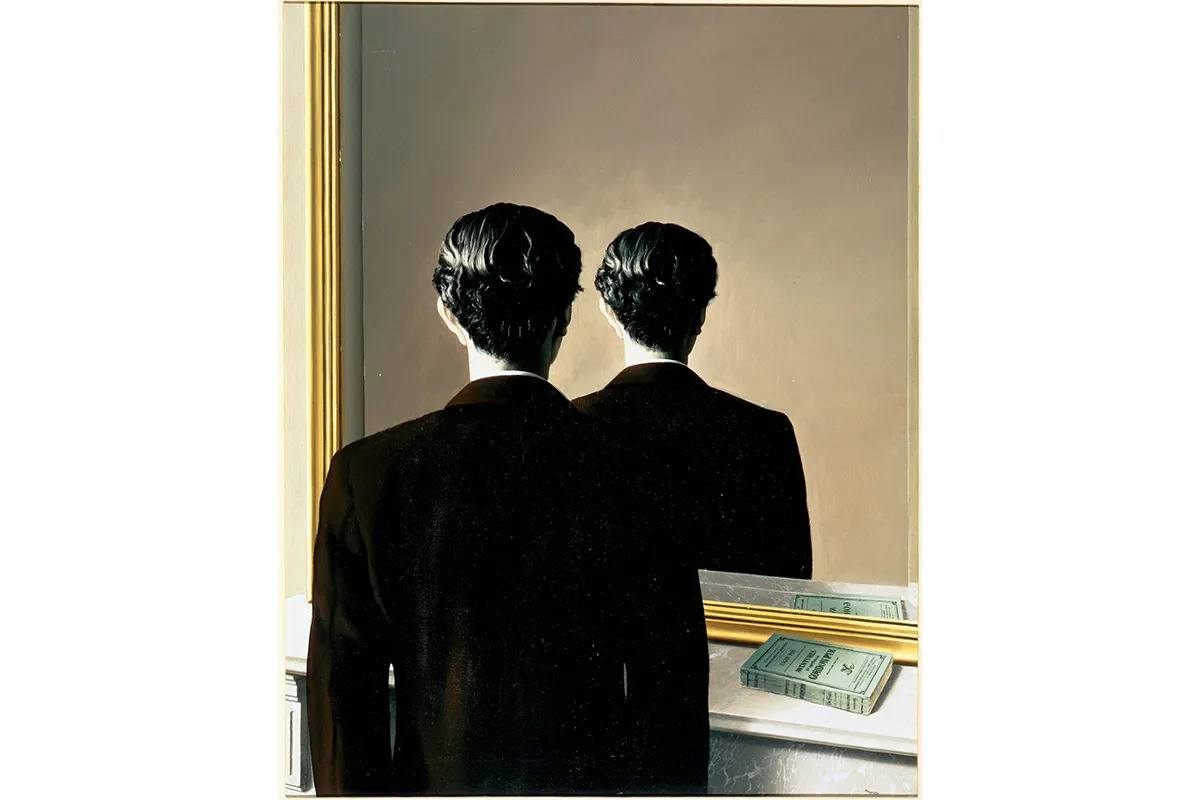

Precisely because they hewed so closely to realism, the works of Belgian painter René Magritte (1898–1967) have become some of the most celebrated in the Surrealist canon. Magritte played with preconceptions of what representational art was supposed to represent. Images such as those of a couple kissing while their heads are draped in white cloth (The Lovers, 1928), a man seeing the back of his head in a mirror (Not to Be Reproduced, 1937), a small locomotive emerging from a fireplace (Time Transfixed, 1938), and a rainstorm of bowler-hatted businessmen falling to earth (Golconda, 1953) ruptured expectations of how subjects and settings cohere, which Magritte made all the more illogical through his matter-of-fact approach.

Magritte’s art didn’t just undermine preconceptions; it also subverted the language we use to describe things. He underscored this directly in an impassive rendering of a tobacco pipe with the legend Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe). Generally known by its caption, it’s actually called The Treachery of Images (1929), a title that evokes how we betray ourselves by ignoring the obvious: that an image of something isn’t the same as the thing itself.

Rene Magritte, Not to Be Reproduced, 1937. Collection of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Photo: Banque d’Images, ADAGP/Art Resource, New York. Artwork © 2024 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Photo: Banque d’Images, ADAGP/Art Resource, New York. Artwork © 2024 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Salvador Dalí

Salvador Dalí (1904–89) became synonymous with Surrealism, not only for signature icons like melting watches or bizarre objects like his Lobster Telephone (1938)—a phone whose handset was sheathed in a crustacean carapace—but also for his theatrical behavior and appearance. More so than Picasso, Dalí was a model of modern art celebrity, which, besides getting him in trouble with Breton for being too famous, also obscured the import of his work.

Frenzied swirls of delirious, if not demented, subject matter were his specialty, seen in paintings like The Persistence of Memory (1931), featuring the aforementioned timepieces, and late-career efforts like The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968–70), which depicts a succession of Venus de Milos receding across a Roman arena. Dalí labeled this approach the “paranoiac-critical” method, which he based on the notion that paranoiacs perceive things that aren’t actually there. Accordingly, his work served as a kind of stream-of-consciousness Rorschach test for viewers.

Ultimately Dalí was his own worst enemy, falling out with Breton and the rest of the Surrealists over his admiration of Hitler and support of Franco during the Spanish Civil War. He also diluted his art by dumping too much of it into the market and prioritized his antics over his oeuvre—becoming, in the end, a caricature of himself.

Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Meret Oppenheim

If Dalí was the artist most closely associated with Surrealism, then Meret Oppenheim made the piece that defined its brand: the fur-lined teacup of Object (1936), a tour de force that was as simple as it was inscrutable. Born in Berlin, Oppenheim (1913–85) became the most renowned of the few women Surrealists due to Object and the lore around its creation. The story begins with Oppenheim in a café with Picasso, who complimented her on a fur-trimmed bracelet she was wearing. Noticing her tea had grown cold, she purportedly replied, “Almost anything can be covered in fur!” before calling over the waiter and asking him for “more fur” as a warm-up.

The same year it was made, Object was included in the “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and became an immediate sensation. Oppenheim, however, was no one-hit wonder: She continued her practice over the next 50 years, an achievement given its due by another MoMA show, a retrospective, in 2022.

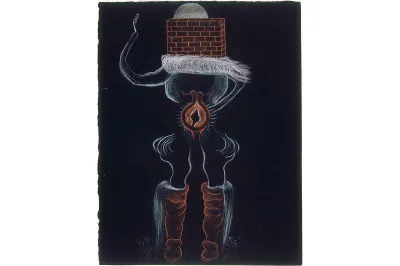

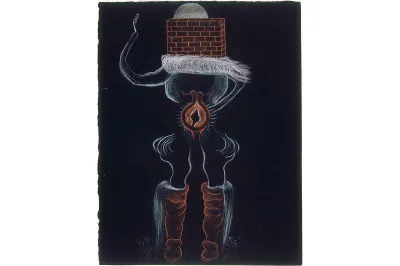

Meret Oppenheim, Couple, 1967. Collection of the Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany. Photo: bpk Bildagentur/Sprengel Museum/Michael Herling | Aline Gwose/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ProLitteris, Zurich. Collection of the Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany. Photo: bpk Bildagentur/Sprengel Museum/Michael Herling | Aline Gwose/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ProLitteris, Zurich. Arp, Miró, and Tanguy

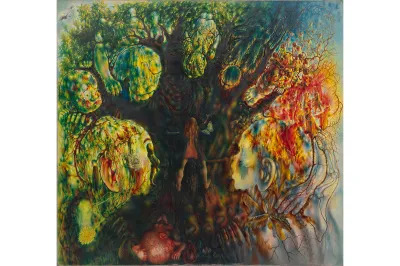

Though very different artists, Jean Arp (1886–1966), Joan Miró (1893–1983), and Yves Tanguy (1900–55) shared a propensity for employing organic forms that hovered between figuration and abstraction, creating a genre of Surrealism—biomorphism—that persists to this day. Biomorphism grew out of automatism, its strange forms emerging from the artists’ subconscious. As Miró himself once explained, “When I stand before a canvas, I never know what I’ll do, and I am the first one surprised at what comes out.”

All three artists used shapes that were at once recognizable and not, leveraging this paradox to evoke irreal dreamscapes. While Arp and Miró flattened their forms, the self-taught Tanguy used chiaroscuro and perspective to give the elements in his paintings a volumetric presence and three-dimensionality, making them appear apparitional. That this same approach found its way into Dalí’s work was no accident: Dalí admitted to Tanguy’s niece that he’d stolen it from her uncle.

Joan Miró, Painting, 1933. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, 2024. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, 2024. -

Surrealism and Photography

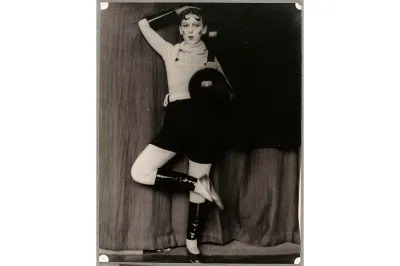

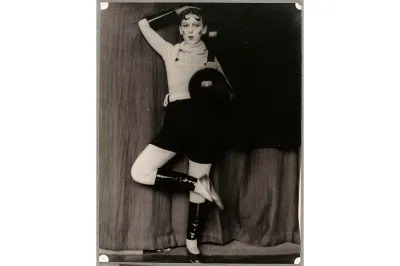

Image Credit: Photo: Copyright © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Estate of Claude Cahun. Though photography is generally associated with the objective recording of reality, Man Ray (1890–1976), Claude Cahun (1894–1954), and Hans Bellmer (1902–75) made it a vital Surrealistic medium.

While Man Ray pursued painting and sculpture, he is best known for photographs that include portraits of Duchamp as Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, and Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), which features his lover and muse, Kiki de Montparnasse, facing away from the camera with her nude back sporting sound holes like those on the bodies of stringed instruments. Man Ray also created surreal images through darkroom experiments, such as exposing objects laid on photosensitive film to create ghostly “Rayograms” and flickering the lights while developing prints to introduce otherworldly, auralike effects.

Like Duchamp, Claude Cahun explored gender bending and in fact made it a consistent part of her work. Anticipating Cindy Sherman by 50 years, she produced performative self-portraits, often in male guises. She also cropped her hair short and even shaved her head, to obscure her sexual identity.

Mannequins figured prominently in Surrealist art, thanks to their uncanniness. And no artist exploited this quality as perversely as Hans Bellmer, whose photos of disarticulated doll parts probed the darkest, most violent corners of eroticism. These “poupées,” as he called them, evoked the Surrealism of the mass killer as laid out in Breton’s declaration that “the simplest surrealist act consists . . . of descending into the street and shooting . . . as much as possible, into the crowd.” Produced during the late 1930s, Bellmer’s images also foreshadowed the abattoir of World War II.

-

Surrealism During the War and After

Image Credit: Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. The one thing, perhaps, that most defined Surrealism during its heyday in the 1920s and ’30s was Breton’s control over it as he anointed and expelled artists and otherwise shaped the group in his image. But for a number of reasons, his role became less important as Surrealism entered the 1940s.

First, World War II altered the dynamics of the movement, turning it inward and less concerned with titillating the public. Second, Surrealism began to spread worldwide as artists fled the Nazi occupation of Europe. Their exile not only transmitted Surrealism’s ideas but also facilitated its eventual irrelevancy. This was especially true in New York, where the presence of Surrealist refugees such as Roberto Matta, Ernst, Tanguy, Masson, and Breton himself kick-started America’s dominance of postwar art by inspiring the Abstract Expressionists.

-

Surrealism in Latin America

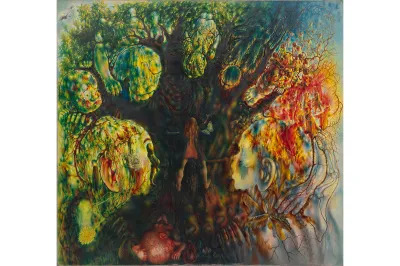

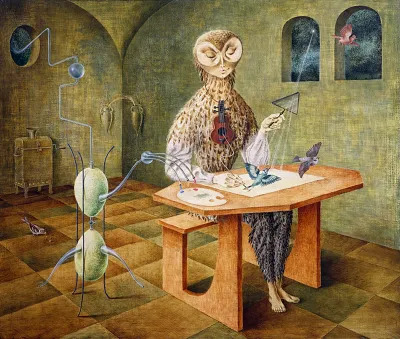

Image Credit: Collection of the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno/Mexico City/Mexico. Photo: Copyright © DeA Picture Library/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © 2024 Remedios Varo, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VEGAP, Madrid. Latin America became fertile ground for Surrealism during the war thanks to a convergence of artists from the region and escapees from Europe. Among the former, the Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (1902–72) combined a wide range of influences into a Cubist-Primitivist-Surrealist mélange that evoked Afro-Cuban culture. He knew Breton and Matisse as well as Picasso, to whom he owed a noticeable debt in paintings like The Eternal Presence (1944), which resembled a chimerical remix of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). The Chilean artist Matta (1911–2002) was another key figure, whose biomorphic compositions would serve as an important bridge between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism.

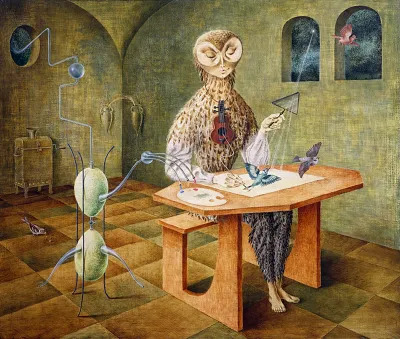

Mexico was a hemispherical hot spot, where Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera presided over an artistic and intellectual milieu that attracted foreigners fleeing World War II, a number of whom—Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Alice Rahon—were women. Kahlo (1907–54) never considered herself a Surrealist (though Breton described her work as a “ribbon around a bomb”); regardless, Kahlo’s self-portraits often employed fantastical metaphors for her inner life. Clearer on this score was the work of Carrington (1917–2011), whose dreamscapes were shot through with shadowy symbolism.

-

Queer Surrealism

Image Credit: Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York. Surrealism harbored several LGBTQ artists whose queerness percolated through their art. This was certainly true of Cahun, but it was also apparent within a circle of gay male painters in New York consisting of Jared French (1905–88), Pavel Tchelitchew (1898–1957), and George Tooker (1920–2011).

French was particularly blatant, surfacing the latent homoeroticism of classical art with friezelike, allegorical tableaus of nude men. On the other hand, Tchelitchew’s psychedelic X-ray mergers of organic and figurative forms played peek-a-boo with the gay burden of hiding in plain sight, while Tooker’s paintings of subway stations and bureaucratic offices combined urban alienation with the paranoia of the closet.

-

The Triumph of Surrealism

Image Credit: Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, New York. As noted above, Surrealism’s assimilation by New York artists became a game changer, though not as Breton had expected. Much as Surrealism supplanted Dada, Abstract Expressionism supplanted Surrealism, though it retained some of the latter’s DNA.

Still, Surrealism as such continued in places like Chicago, with the reveries of Gertrude Abercrombie and the macabre magic realism of Ivan Albright. In Egypt, Surrealism remained a vital force into the late 1950s, as painters like Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar used their work to extoll Egyptian nationalism under the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser.

And Surrealist tendencies persisted as art increasingly harvested popular culture through the 1960s and beyond. The revival of figurative painting in the 21st century has also leaned heavily into Surrealist tropes.

Surrealism’s echoes still reverberate in a much broader sense as well. Social media, along with virtual reality and artificial intelligence technologies, have made the distinction between life online and off all but disappear, resulting in a digital manifestation of Breton’s “super-reality.” Surrealism has indeed remade the world, albeit in ways that he scarcely could have imagined.

What Was Surrealism?

Breton defined Surrealism as a way to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” He recast it as an artistic enterprise with his 1928 publication Surrealism and Painting. By then, artists such as Jean Arp, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, René Magritte, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy had been drawn into his orbit.

Stylistically, Surrealism ranged from the quasi-abstraction of Miró to Magritte’s deadpan realism. Originally centered in Paris, it became global in scope, spilling over to the Americas and Asia. Reacting to the carnage of World War I, the movement attacked rationalism and social decorum, upending longstanding artistic precepts and subverting conventional sexual mores with misogynistic élan. Even so, Surrealism attracted a significant cohort of female artists, among them Meret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning, Claude Cahun, and Leonora Carrington.

The Surrealists reveled in a discontinuity best summarized by a line from the 1868 novel Les Chants de Maldoror, which described a “chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table.” This idea became Surrealism’s credo, codified by the collaborative genre known as the cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse). Resembling a game of telephone, but played with drawings, cadavre exquis involved passing a piece of paper around a group of artists. Each would render part of a figure, then hide it by folding the sheet over. Other participants would follow suit, and the result when revealed was predictably disjointed.

Surrealism, Freud, and Automatism

Surrealism was deeply indebted to Sigmund Freud. His belief that the mind could be unlocked through psychoanalytical methods such as the interpretation of dreams made a huge impact on Breton, who’d attended medical school and developed an interest in mental illness before he became a writer. Serving in the French army’s medical corps on the Western Front in World War I, Breton was stationed at a ward in Nantes that treated soldiers for shell shock (what we would today call PTSD), where he applied Freud’s theories while caring for patients.

Breton believed the subconscious could unshackle art from its conventions through automatism, a process that surrendered deliberation to an unimpeded flow of imagination. He described it as a “pure state by which one proposes to express . . . the actual functioning of thought . . . in the absence of any control exercised by reason.” Here again he was indebted to Freud, who pioneered “free association,” which encouraged patients to relay feelings, memories, and reveries in an unregulated rush of words.

André Masson (1896–1987) developed the artistic application of this method with a series of drawings begun in 1924, characterized by agglomerations of lines produced in a fugue state. Automatism would eventually become foundational to Abstract Expressionism in the post–World War II era.

Proto-Surrealism

While we think of Surrealism as a 20th-century phenomenon, its roots in art reach much farther back. For much of European art history, depictions of heaven and hell were a constant theme, and in this respect, portrayals of otherworldly planes intersecting our own were an accepted fact of pictorial organization.

Medieval and Renaissance Art

All such art was arguably surreal in this sense, but there were instances of what could be called proto-Surrealism, particularly in the work of Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516), a Dutch/Netherlandish painter whose phantasmagoric compositions are among the most canonical in Western art. Paintings like The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) were much admired by the Surrealists for their bizarre scenery and chaotic juxtaposition of disparate images.

The fanciful portraits of the Italian Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526–93) were also proto-Surrealist, combining still life and trompe l’oeil to cobble imaginary sitters out of objects related to them (a librarian made of books, a cook fashioned out of victuals, and so on).

Romanticism

Surrealism could be considered a backlash to large historical forces—the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution—that developed in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries. The former held that religion and faith must relinquish themselves to the power of reason, effectively severing a connection between the physical and metaphysical that Surrealism would later try to repair.

Surrealism rejected Enlightenment beliefs, but it wasn’t the first movement to do so. In the early 19th century, Romanticism swept across the Continent, its proponents arguing that relying on reason alone shortchanged individual agency by ignoring sensation, both good and bad. Among the artists within its ranks were three—William Blake, Henry Fuseli, and Francisco Goya—whose work could be considered proto-Surrealistic.

A poet as well as an artist, Blake (1757–1827) conjured ecstatic visions of figures set against stars and planetary orbs, radiating coronas of cosmic light that metaphorically burst the straitjacket of logic. Blake critiqued reason in hand-colored engravings like Newton (1795), which depicts the eponymous titan of science seated naked on a rock, bending over a scroll with compass in hand, so fixated on his calculations that he’s blind to everything else.

Fuseli (1741–1825) was a Swiss artist whose crepuscular masterpiece, The Nightmare (1781), plumbed the erotic depths of dreams a century before Freud. It pictures a woman in a diaphanous gown lying prostrate on a bed as a satanic incubus sits on her chest. On the left, a blind horse pokes its head through a curtain. The sexual overtones of The Nightmare are as disturbing as they are unmistakable; the same overtones suffuse Fuseli’s other works, including studies of women whose tinge of fetishistic obsession presaged the same within Surrealism.

One of the iconic names in Western art, Goya (1746–1828) channeled the benighted conditions of late 18th– and early 19th-century Spain as it lay in the smothering grip of the Catholic Church. In 1799 he published The Caprices, a folio of aquatints depicting Spain’s crippling backwardness as a series of stark tableaux populated by hideous dwarfs, cadaverous hags, witches, and other abominations. The signature image of the collection shows a man, head down on a table, beset by scores of bats, cats, and owls. Its caption, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” speaks to the limits of the Enlightenment project to reform behavior.

Symbolism

In the late 19th century, another group of artists likewise anticipated Surrealism. Calling themselves Symbolists, they explored aspects of the human condition as dreamlike allegories.

Odilon Redon (1840–1916) is probably the most widely recognized Symbolist thanks to his “noirs,” a series of lithographs and charcoals begun in the 1880s. Among the most extraordinary was The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity (1882). Much of Redon’s work was inspired by writers like Edgar Allan Poe, to whom this rendering of an eyeball ascending the sky was dedicated.

The work of Gustave Moreau (1826–98) was equally hallucinatory, suffusing scenes from Greek mythology and the Bible with a lysergic air of exoticism. His most famous canvas, The Apparition (1874–76), transforms the New Testament tale of John the Baptist’s head being delivered on a platter to Salome into a deliriously decadent apparition of his severed pate floating in front of the barely clothed recipient.

Post-Impressionism

While Symbolism functioned as a unique chapter in art, it was also the result of the Post-Impressionist context in which it developed. Marquee names of the period—Paul Gaugin, Edvard Munch, and Vincent van Gogh—crossed over into Symbolism.

This was especially true of Gaugin, whose Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake (1889) leavened a meditation on good versus evil with a generous dollop of self-regard, and Munch, whose combination of Symbolism and Expressionism resulted in that veritable logo for angst, The Scream (1893). Van Gogh, meanwhile, psychologically supercharged his landscapes and genre scenes, employing frenetic brushwork as a kind of borderline automatism.

James Ensor

A contemporary of the artists above, James Ensor (1860–1949) also foreshadowed Surrealism. Ensor spent much of his life in Ostend, a resort on the Flanders coast. His family ran a gift emporium there catering to tourists, and it was especially busy during the city’s annual carnival, when the shop sold masks to revelers. These items featured prominently in Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1889), which transplants the Gospel tale of Jesus’s triumphal arrival into Jerusalem to the Belgian capital of Ensor’s day. Jesus is seen in a parade led by a boisterous crowd wearing grotesque masks. Even more uncanny were paintings like Skeletons Warming Themselves (1889), of a group of costumed skeletons gathered around a stove.

Giorgio de Chirico

While Freud provided the theoretical foundation for Surrealism, Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978) supplied its visual template, arguably exercising an even greater influence than Freud on the Surrealists. His work predated Dada by several years, with paintings like The Enigma of the Oracle going as far back as 1910. He dubbed his approach pittura metafisica (metaphysical art).

A typical de Chirico composition centered on a desolate Italian piazza bounded by colonnades, towers, and other elements of classical architecture, though factories appeared occasionally in the background. His scenes were for the most part devoid of people, populated instead by an odd assortment of objects that included Greco-Roman statuary, mannequins, and cryptic geometrical solids. He used sharp contrasts between light and dark, and long, menacing shadows loomed throughout. His sharply titling perspective led the eye into a kind of spatial purgatory, a trope adopted later by Tanguy, Dalí, and others.

De Chirico’s work was enthusiastically embraced by Breton, who credited it with “preserving for eternity the memory of the true modern mythology.” However, Breton’s view of de Chirico cooled considerably after 1928, by which time the latter had abandoned metaphysical art, turning instead to an odd, and often clunky, blend of classical and baroque motifs.

De Chirico’s most famous paintings spoke to the anxieties of the Industrial Age by evoking a curdled nostalgia for the certainties of antiquity. To this extent, they always expressed the artist’s skepticism toward modernity, a gimlet view that would blossom in his later retardataire style. Still, metaphysical art was ambiguous enough to earn an essential spot within the avant-garde.

Dada and Surrealism

Surrealism initially began as a breakaway faction of the Dada movement, precipitated by arcane philosophical disputes between Breton and the Dadaist provocateur Tristan Tzara (1896–1963). Nonetheless, both Dadaism and Surrealism grew out of the same horrified reaction to the butchery of WW1 and the same contempt for capitalism and bourgeois propriety.

Dada originated when a group of writers and poets—Tzara, Emmy Hennings, Hugo Ball, and Marcel Janco—came together in Zurich during the winter of 1915, by which time the Western Front had descended into a stalemate. The group assembled at a local club called the Cabaret Voltaire for evenings of nonsensical recitals and other performative acts. To them, absurdism seemed the only sane response to a Europe gone mad. Dada soon established itself in other cities including Berlin, Cologne, and New York. Several artists from these centers—Max Ernst and Jean Arp from Germany, Man Ray from America—would join Breton’s Surrealist camp.

Tzara was key to Dada’s expansion to Paris, where he moved in 1919 to join the staff of Littérature, a magazine edited by Breton; not surprisingly, its pages became a forum for the arguments between them. Their disagreement revolved around the efficacy of art and culture in the aftermath of world-shattering events. Tzara took a nihilistic view that averred the pointlessness of aesthetics. Rejecting Tzara’s anti-art outlook, Breton believed that a new kind of order—Surrealism—could reconstruct a society unraveled by war.

Things came to a head in 1921 with a mock trial presided over by Breton. Ostensibly the defendant was critic Maurice Barrès, a French anarchist turned right-wing apologist for whom Tzara served as a friendly witness. As the proceedings went on, the indictment against Barrès was redirected toward Dada itself, signaling its end as an artistic force.

The Rise of Surrealism

Whatever else it was, Surrealism was very much a product of the interwar years, which are now often considered a lull within the same global conflagration. The liminal state of a Continent suspended between peace and war was reflected by the gap between reality and dream that Surrealism mined in the 1920s and ’30s. During these years, Surrealism went from being a marginal idea to becoming a popular-culture fixture of the era. Two exhibitions charted this evolution.

On November 13, 1925, the Exposition Surréaliste, the first-ever survey of Surrealist art, opened at Galerie Pierre Colle in Paris, featuring Arp, Klee, Man Ray, Ernst, Miró, de Chirico, Masson, and Pierre Roy, as well as Pablo Picasso, who’d incongruously submitted one of his Cubist paintings. (Picasso’s inclusion was due to Breton’s acute desire to ally the world’s most famous modern artist to the Surrealist cause.) Though these artists had all previously shown their work, the exhibition marked their debut under Breton’s banner.

While the 1925 show brought together the core Surrealist group, the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme of 1938 went farther afield. Co-curated by Breton and the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, with Marcel Duchamp, Dalí, and Ernst serving as advisers, the exhibit opened on January 17 at Georges Wildenstein’s Galérie Beaux-Arts in Paris with nearly 300 works by 60 contributors from 14 countries.

Man Ray designed the exhibit’s lighting while the Austrian-Mexican artist and writer Wolfgang Paalen (1905–59) supervised an entryway installation composed of foliage and the Dalí centerpiece Rainy Taxi, an ivy-covered car with a mannequin seated inside under spraying water. Though he never joined the Surrealists officially, Duchamp created the final room, for which he hung hundreds of coal bags stuffed with newspapers from the ceiling.

During the evening opening, the lights went out, forcing attendees to view the show with flashlights. In terms of scale and participants involved, the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme demonstrated the movement’s arrival as a cultural phenomenon.

Who Were the Surrealists?

The number of artists identifying themselves as Surrealists grew remarkably in the 1920s and ’30s and included such far-flung practitioners as Tokyo-based Koga Harue, who painted meditations on the industrialization—and militarization—of Japan. But several individuals were mainly responsible for setting the various directions Surrealism would take.

Max Ernst

The artist whose work best encapsulated the shift from Dada to Surrealism was Max Ernst (1891–1976), who was born near Cologne. In 1914 he was drafted into the German army, and the trauma he suffered during the war became the defining experience of his art. Based in Cologne during the early 1920s, Ernst fashioned collages out of found illustrations that he overpainted by hand. One example involved a biology-class chart depicting plant cells undergoing mitosis. Turning it upside down, Ernst added a black backdrop and other elements that transformed these cells into circus performers on a tightrope.

Works such as this were consistent with the anarchistic spirit of Dada, but in 1923 Ernst moved in a more enigmatic direction, turning from collage to painting with the impenetrable seaside vista Woman, Old Man, and Flower (1923–24). Begun in Cologne, it was later modified in Paris with the addition of the mysterious, fan-headed woman dominating the composition once Ernst joined the Surrealists there.

Ernst developed techniques that transferred serendipitous, collagelike textures to his work by rubbing or scouring paper or still-wet canvas placed over pieces of wood, window screen, or string. He also laid glass sheets over freshly applied oils, then pulled them up to produce chance surface alterations. Both practices figured prominently in his wartime masterpiece, Europe After the Rain II (1940–42), which imagined the Continent as a blasted postapocalyptic landscape.

René Magritte

Precisely because they hewed so closely to realism, the works of Belgian painter René Magritte (1898–1967) have become some of the most celebrated in the Surrealist canon. Magritte played with preconceptions of what representational art was supposed to represent. Images such as those of a couple kissing while their heads are draped in white cloth (The Lovers, 1928), a man seeing the back of his head in a mirror (Not to Be Reproduced, 1937), a small locomotive emerging from a fireplace (Time Transfixed, 1938), and a rainstorm of bowler-hatted businessmen falling to earth (Golconda, 1953) ruptured expectations of how subjects and settings cohere, which Magritte made all the more illogical through his matter-of-fact approach.

Magritte’s art didn’t just undermine preconceptions; it also subverted the language we use to describe things. He underscored this directly in an impassive rendering of a tobacco pipe with the legend Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe). Generally known by its caption, it’s actually called The Treachery of Images (1929), a title that evokes how we betray ourselves by ignoring the obvious: that an image of something isn’t the same as the thing itself.

Salvador Dalí

Salvador Dalí (1904–89) became synonymous with Surrealism, not only for signature icons like melting watches or bizarre objects like his Lobster Telephone (1938)—a phone whose handset was sheathed in a crustacean carapace—but also for his theatrical behavior and appearance. More so than Picasso, Dalí was a model of modern art celebrity, which, besides getting him in trouble with Breton for being too famous, also obscured the import of his work.

Frenzied swirls of delirious, if not demented, subject matter were his specialty, seen in paintings like The Persistence of Memory (1931), featuring the aforementioned timepieces, and late-career efforts like The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968–70), which depicts a succession of Venus de Milos receding across a Roman arena. Dalí labeled this approach the “paranoiac-critical” method, which he based on the notion that paranoiacs perceive things that aren’t actually there. Accordingly, his work served as a kind of stream-of-consciousness Rorschach test for viewers.

Ultimately Dalí was his own worst enemy, falling out with Breton and the rest of the Surrealists over his admiration of Hitler and support of Franco during the Spanish Civil War. He also diluted his art by dumping too much of it into the market and prioritized his antics over his oeuvre—becoming, in the end, a caricature of himself.

Meret Oppenheim

If Dalí was the artist most closely associated with Surrealism, then Meret Oppenheim made the piece that defined its brand: the fur-lined teacup of Object (1936), a tour de force that was as simple as it was inscrutable. Born in Berlin, Oppenheim (1913–85) became the most renowned of the few women Surrealists due to Object and the lore around its creation. The story begins with Oppenheim in a café with Picasso, who complimented her on a fur-trimmed bracelet she was wearing. Noticing her tea had grown cold, she purportedly replied, “Almost anything can be covered in fur!” before calling over the waiter and asking him for “more fur” as a warm-up.

The same year it was made, Object was included in the “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and became an immediate sensation. Oppenheim, however, was no one-hit wonder: She continued her practice over the next 50 years, an achievement given its due by another MoMA show, a retrospective, in 2022.

Arp, Miró, and Tanguy

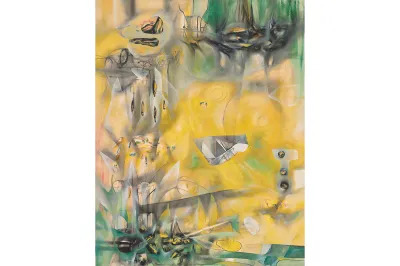

Though very different artists, Jean Arp (1886–1966), Joan Miró (1893–1983), and Yves Tanguy (1900–55) shared a propensity for employing organic forms that hovered between figuration and abstraction, creating a genre of Surrealism—biomorphism—that persists to this day. Biomorphism grew out of automatism, its strange forms emerging from the artists’ subconscious. As Miró himself once explained, “When I stand before a canvas, I never know what I’ll do, and I am the first one surprised at what comes out.”

All three artists used shapes that were at once recognizable and not, leveraging this paradox to evoke irreal dreamscapes. While Arp and Miró flattened their forms, the self-taught Tanguy used chiaroscuro and perspective to give the elements in his paintings a volumetric presence and three-dimensionality, making them appear apparitional. That this same approach found its way into Dalí’s work was no accident: Dalí admitted to Tanguy’s niece that he’d stolen it from her uncle.

Surrealism and Photography

Though photography is generally associated with the objective recording of reality, Man Ray (1890–1976), Claude Cahun (1894–1954), and Hans Bellmer (1902–75) made it a vital Surrealistic medium.

While Man Ray pursued painting and sculpture, he is best known for photographs that include portraits of Duchamp as Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, and Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), which features his lover and muse, Kiki de Montparnasse, facing away from the camera with her nude back sporting sound holes like those on the bodies of stringed instruments. Man Ray also created surreal images through darkroom experiments, such as exposing objects laid on photosensitive film to create ghostly “Rayograms” and flickering the lights while developing prints to introduce otherworldly, auralike effects.

Like Duchamp, Claude Cahun explored gender bending and in fact made it a consistent part of her work. Anticipating Cindy Sherman by 50 years, she produced performative self-portraits, often in male guises. She also cropped her hair short and even shaved her head, to obscure her sexual identity.

Mannequins figured prominently in Surrealist art, thanks to their uncanniness. And no artist exploited this quality as perversely as Hans Bellmer, whose photos of disarticulated doll parts probed the darkest, most violent corners of eroticism. These “poupées,” as he called them, evoked the Surrealism of the mass killer as laid out in Breton’s declaration that “the simplest surrealist act consists . . . of descending into the street and shooting . . . as much as possible, into the crowd.” Produced during the late 1930s, Bellmer’s images also foreshadowed the abattoir of World War II.

Surrealism During the War and After

The one thing, perhaps, that most defined Surrealism during its heyday in the 1920s and ’30s was Breton’s control over it as he anointed and expelled artists and otherwise shaped the group in his image. But for a number of reasons, his role became less important as Surrealism entered the 1940s.

First, World War II altered the dynamics of the movement, turning it inward and less concerned with titillating the public. Second, Surrealism began to spread worldwide as artists fled the Nazi occupation of Europe. Their exile not only transmitted Surrealism’s ideas but also facilitated its eventual irrelevancy. This was especially true in New York, where the presence of Surrealist refugees such as Roberto Matta, Ernst, Tanguy, Masson, and Breton himself kick-started America’s dominance of postwar art by inspiring the Abstract Expressionists.

Surrealism in Latin America

Latin America became fertile ground for Surrealism during the war thanks to a convergence of artists from the region and escapees from Europe. Among the former, the Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (1902–72) combined a wide range of influences into a Cubist-Primitivist-Surrealist mélange that evoked Afro-Cuban culture. He knew Breton and Matisse as well as Picasso, to whom he owed a noticeable debt in paintings like The Eternal Presence (1944), which resembled a chimerical remix of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). The Chilean artist Matta (1911–2002) was another key figure, whose biomorphic compositions would serve as an important bridge between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism.

Mexico was a hemispherical hot spot, where Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera presided over an artistic and intellectual milieu that attracted foreigners fleeing World War II, a number of whom—Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Alice Rahon—were women. Kahlo (1907–54) never considered herself a Surrealist (though Breton described her work as a “ribbon around a bomb”); regardless, Kahlo’s self-portraits often employed fantastical metaphors for her inner life. Clearer on this score was the work of Carrington (1917–2011), whose dreamscapes were shot through with shadowy symbolism.

Queer Surrealism

Surrealism harbored several LGBTQ artists whose queerness percolated through their art. This was certainly true of Cahun, but it was also apparent within a circle of gay male painters in New York consisting of Jared French (1905–88), Pavel Tchelitchew (1898–1957), and George Tooker (1920–2011).

French was particularly blatant, surfacing the latent homoeroticism of classical art with friezelike, allegorical tableaus of nude men. On the other hand, Tchelitchew’s psychedelic X-ray mergers of organic and figurative forms played peek-a-boo with the gay burden of hiding in plain sight, while Tooker’s paintings of subway stations and bureaucratic offices combined urban alienation with the paranoia of the closet.

The Triumph of Surrealism

As noted above, Surrealism’s assimilation by New York artists became a game changer, though not as Breton had expected. Much as Surrealism supplanted Dada, Abstract Expressionism supplanted Surrealism, though it retained some of the latter’s DNA.

Still, Surrealism as such continued in places like Chicago, with the reveries of Gertrude Abercrombie and the macabre magic realism of Ivan Albright. In Egypt, Surrealism remained a vital force into the late 1950s, as painters like Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar used their work to extoll Egyptian nationalism under the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser.

And Surrealist tendencies persisted as art increasingly harvested popular culture through the 1960s and beyond. The revival of figurative painting in the 21st century has also leaned heavily into Surrealist tropes.

Surrealism’s echoes still reverberate in a much broader sense as well. Social media, along with virtual reality and artificial intelligence technologies, have made the distinction between life online and off all but disappear, resulting in a digital manifestation of Breton’s “super-reality.” Surrealism has indeed remade the world, albeit in ways that he scarcely could have imagined.

Taylor Swift Flew 178,000 Miles Last Year, and This College Student Can Show You Where

Lewis Hamilton Lights Up the Empire State Building at Mercedes AMG Petronas F1 and WhatsApp Party

TikTok at risk as European Commission President calls it a ‘Danger’ amid ban buzz

Derby Draws Crowd, but Churchill Downs Cashes in on Web, Casinos