In the United States, the 1970s were known as the malaise decade, nowhere more so than in New York City, where the white middle class had fled the Five Boroughs along with manufacturing and shipping, leaving a tax base that slipped into a death spiral even as the cost of services and social programs increased. But of all the years during that benighted era, 1977 marked a nadir in the city’s fortunes: On the night of July 13–14, a blackout plunged New York into darkness, precipitating a widespread outbreak of looting and vandalism; the following month, David Berkowitz, aka the Son of Sam, was arrested for a 12-month killing spree that left eight people dead; and during coverage of the World Series that October, a helicopter camera brought us the spectacle of a block being consumed by fire next to Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, where landlords had been burning down abandoned buildings to collect insurance money.

Unnoticed amidst this civic unraveling was a group exhibition titled “Pictures,” which opened in September of 1977 at Artists Space, one of several nonprofit galleries that had sprung up to cultivate emerging talent. Featuring just five artists (Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, and Philip Smith) working variously in painting, sculpture, drawing, photography, and film, the exhibit focused on how mass media and popular culture had transformed the general understanding of imagery through its transmission by photographs, movies, and television. While “Pictures” attracted the attention of only a slice of an art world that was small and localized compared with now, the show, and a generation of artists attached to its name, proved to be an inflection point for art through the rest of the century and into our own.

-

Who Were the Artists of the Pictures Generation?

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © Estate of Jack Goldstein. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. As the moniker implies, the term Pictures Generation (which also included Sarah Charlesworth, Barbara Kruger, Allan McCollum, Matt Mullican, Richard Prince, Walter Robinson, Cindy Sherman, David Salle, Laurie Simmons, James Welling, and a host of others) didn’t denote a style so much as it signaled the advent of a cohort born during America’s postwar baby boom. (They weren’t alone, but more on that later.) They ascended alongside the political forces that would ultimately yield the Reagan revolution, which dismantled the liberal, New Deal order, and while any direct correlation with the Pictures Generation is debatable, its members did manage to reshape the art world largely thanks to Reagan’s reconfiguration of America.

-

A Watershed Moment

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © Barbara Kruger, courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers. Digital image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. The Pictures Generation arrived at a time when New York was still considered the center of artistic production, and artists—and especially critics—still clung to the idea of pushing creative boundaries much as they had throughout the breakthroughs of 20th-century modernism. Both notions would be derailed by an art market spurred on by tax cuts and a resurgent Wall Street under Reagan. While rising and falling over the following 50 years, this boom would ultimately morph into a globalized entity wherein market success, rather than critically sanctioned stylistic progress, determined important art.

As one of the first groups of artists to benefit from this economic largesse, the Pictures Generation arguably initiated a chain of causality that eventually resulted in the ahistorical character of contemporary art today. Nobody, not least the Pictures Generation, could foresee the developments to come, but in retrospect, one could trace them back to that moment in the fall of 1977.

-

The 1970s New York Art World

Image Credit: Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images. New York’s art scene during the 1970s was conditioned by the same economic travails afflicting the city, though not entirely for the worse. As much as NYC’s deindustrialization may have been a bane to its citizenry, it proved to be a boon to artists thanks mainly to collapsing rents that produced cheap studio space, especially in the empty lofts of lower Manhattan.

NYC’s financial implosion was echoed by a concomitant chill in the art market following the buoyant buying of the early to mid 1960s, when Pop Art, and to a lesser extent Minimalism, excited collectors looking for alternatives to Abstract Expressionism. Yet the low cost of living and the presence of alternative, taxpayer-funded showcases like the one that hosted “Pictures” permitted a sense of creative freedom among many artists, giving them the luxury of rejecting the commercial gallery system.

During the late 1960s and early ’70s, this attitude sparked a decentered and dematerialized practice that emphasized idea over form, leading to new genres such as Conceptualism, earthworks, installation/process art, video art, and performance. To distinguish them from Minimalism (which, while largely sculptural and highly finished, was no less reductive), these approaches were lumped under the umbrella term Postminimalism, setting the stage for a radical endgame in which art reached a kind of degree zero of pure discourse.

This notion was as nihilistic as it was liberating, however, so as the decade wore on, the search for a way out of the strictures of Postminimalism began. Eclecticism became an art-world buzzword, but there was still a desire for a return to a more viewer-friendly and concrete expression that would comport with the narrative Postminimalism had fashioned for itself—a longing that “Pictures” aimed to address.

-

The “Pictures” Show

Image Credit: D. James Dee. Digital image courtesy of Artists Space, New York. “Pictures” signaled a return to representationalism, though the latter had hardly disappeared, even during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. Scores of artists (Barkley Hendricks, Alex Katz, Catherine Murphy, Alice Neel, Philip Pearlstein, Fairfield Porter, and Bob Thompson, to name just a few) worked in a diverse spectrum of figurative styles ranging from expressionistic to realistic. Moreover, Pop Art and photorealism served as antecedents for the Pictures Generation—the former because it gathered motifs from mass culture, the latter because it mediated painting and sculpture through the prism of photography.

The “Pictures” exhibition, however, framed its premise within the context of Conceptualism. Just as Conceptual Art severed object and idea, “Pictures” attempted to separate representation “from the tyranny of the represented,” as show organizer Douglas Crimp put it. This paradoxical assertion cloaked a reaction against Postminimalism in its own tenets, but Crimp’s argument was also rooted in the broader context in which the Pictures artists had come of age.

-

The Postwar Roots of the Pictures Generation

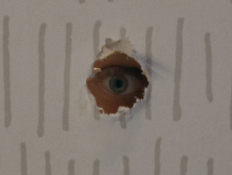

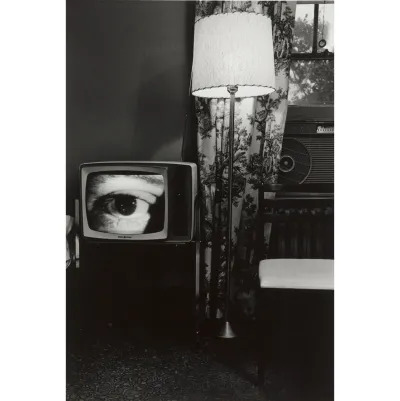

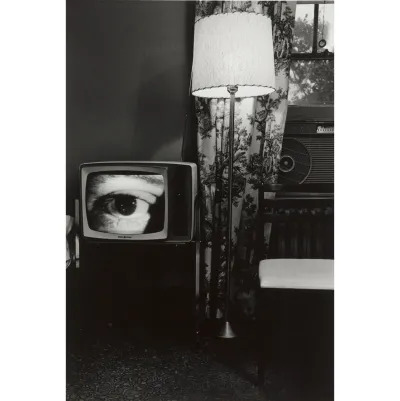

Image Credit: Photograph copyright © Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Luhring Augustine, New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/ Art Resource, New York. Pictures Generation artists came largely from white, middle-class backgrounds, growing up in the suburbs within a media monoculture comprising a limited array of broadcast television channels (most cities had only three). From childhood onward, they were exposed to a diet of sitcoms, Westerns, and police procedurals that reinforced white male privilege. Postwar television also instantaneously relayed news on monumental events such as the civil rights movement, the Kennedy assassinations, and the Vietnam War, delivering shocks to the system that helped to fray the societal norms coming out of World War II. In a way barely conceivable today, television had the power to tie the country together—and to break it apart as well. This underlying tension was mirrored within the Pictures aesthetic.

Television, along with Hollywood films, glossy magazines, and the blandishments of Madison Avenue, produced a pervasive landscape of memes far more lasting than those generated online today. It’s often said that the members of the Pictures Generation were the first artists to have grown up with television; this meant that they were the first to know life as a wholly manufactured phenomenon designed to stimulate consumerism, making their experience a kind of late-capitalist irreality—a “tyranny of the represented,” per Crimp. The Pictures Generation’s shaping by mass media was far more cohesive and top-down than it is for the young of today and also different from the enculturation of older Pop artists, like Andy Warhol (born in 1928), who viewed popular culture as a smorgasbord of subjects rather than as a totalizing regime.

-

The Return of Representationalism in the 1970s

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © 2024 Robert Moskowitz/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image copyright © Whitney Museum of American Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, New York. As previously noted, artists continued to pursue representational art in different ways throughout the postwar period, though there were several epiphenomenal feints in the direction of its resurgence that presaged “Pictures” within 1970s art.

For example, much as Jasper Johns did with his targets and flags, the Pattern and Decoration (P&D) movement (whose adherents included Tina Girouard, Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, and Miriam Schapiro) attempted to split the difference between the recognizable and the abstract by employing repetitive motifs derived from textiles and wallpaper. At the same time, feminist artists sustained representationalism as they attacked traditional depictions of women through painting (Judy Chicago, Joan Semmel), body art (Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke) and other genres.

Representationalism hadn’t completely disappeared within Postminimalism either. The otherwise ephemeral manifestations of performance art were documented in photographs and videos that became de facto figurative artworks. This practice almost immediately spun off into Photo-Conceptualism, a form separate from the recording of actions staged for an audience. Artists such as William Wegman and, more influentially for the Pictures Generation, John Baldessari, often used color film and serial imagery to produce works that were likewise representational, and artists utilizing video as a discrete genre did the same.

Yet another subset of Postminimalists—Sol Lewitt, Mel Bochner, and Dorothea Rockburne, among others—had been applying epistemological systems (linguistics, mathematics) to abstract paintings and sculptures, but here, too, certain artists managed to sneak representation into the mix. Jonathan Borofsky’s drawings, sculptures, and installations were taken from dreams, but he also framed them within a conceit of counting toward infinity so that each object was numbered according to its appearance in the scheme. Far more obscure was the work of Pinchas Cohen Gan, an Israeli-Moroccan artist living in New York who abandoned strict Conceptualism by introducing an enigmatic, everyman figure into paintings done on tablecloths; sketchy and minimalistic, these compositions formulated art as a kind of science. Jennifer Bartlett arranged panels within grids that featured content algorithmically advancing from geometric shapes to renderings, for example, of landscapes resembling eight-bit computer graphics.

Elsewhere, Minimalist sculptor Joel Shapiro deviated from the non-referential, specific object template of Donald Judd and Dan Flavin by scattering small, house-shaped objects within sprawling installations, while Robert Moskowitz plunked isolated silhouettes of Cadillac tail fins and Chicago’s Wrigley Building into allover fields of gestural marks. Other echoes of Postminimalism—textualization, process art—found their way into the figurative paintings of Neil Jenney and Joe Zucker.

By 1977, then, a renewal of representational art was very much in the air, though it took “Pictures” to attempt a cohesive theory of the case. A year later, more-established venues tried something similar, with the Whitney and the New Museum mounting exhibitions respectively titled “New Image Painting” and “‘Bad’ Painting” though neither included artists from the Pictures Generation.

-

The European Influence on the Pictures Generation

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © 2024 The Estate of Sigmar Polke, Cologne/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image copyright © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Aside from the dynamics of postwar America in which they’d come of age, the Pictures Generation was very much impacted by contemporaneous currents in Europe, especially the New Wave cinema and critical writings coming out of France.

Filmmakers such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, and Claude Chabrol rejected the polished look of studio productions, using lightweight cameras and spontaneous cinematography to give their movies the feel of documentary realism. They subverted conventional montage with edits that disrupted narrative flow. The look of these films, and the meta-commentaries they often made on Hollywood genres such as film noir, became touchstones for several artists from the Pictures Generation.

Just as pertinent were the theoretical musings of the French philosophes who arose during the sociopolitical clamor of May 1968—among them Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, and Jean Baudrillard. Their texts, though highly varied, interrogated the articulation of meaning itself, positing that it was governed—and was a function of—institutional power. These ideas, labelled Poststructuralism by American academics, resonated with the Pictures Generation’s ironic realization that the formative years of its members had been an existential immersion into artifice.

The Pictures Generation was also aware of the work in Germany of Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, who had hatched a kind of tongue-in-cheek movement they dubbed Capitalist Realism. This, too, was aimed at the “tyranny of the represented” seen in the projection of American pop culture across the Continent as a form of soft power during the Cold War.

-

The Pictures Generation Arrives

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © The Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Digital Image copyright © Museum Associates/ LACMA/ Licensed by Art Resource, New York. The Pictures Generation distinguished itself from previous schools in other ways as well. Women artists—Sarah Charlesworth, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman, and Laurie Simmons among them—played a significant role, injecting a strain of feminism into the Pictures sensibility, albeit one that was less interested in female empowerment than in unpacking the ways in which images of women were exploited to foster consumption. (Interestingly, if somewhat predictably, the larger visibility of women artists within the Pictures Generation was met by a backlash from some of their male peers.)

Migration to New York had always been a feature of the city’s art scene; artists from all over the country and world came there to find their stylistic footing. But here, too, the Pictures Generation differentiated itself to a certain degree, as some members shared specific points of origin that forged their sensibilities outside NYC. Several of them—Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Matt Mullican, David Salle, and James Welling—had graduated from the California Institute for the Arts (CalArts), of which John Baldessari had been a founding faculty member. Then there was the so-called Buffalo Invasion, which included Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo among its ranks. All graduates of the State University of New York at Buffalo, they had coalesced around a regional alternative space called Hallwalls before coming to New York.

-

Pictures Generation Peers

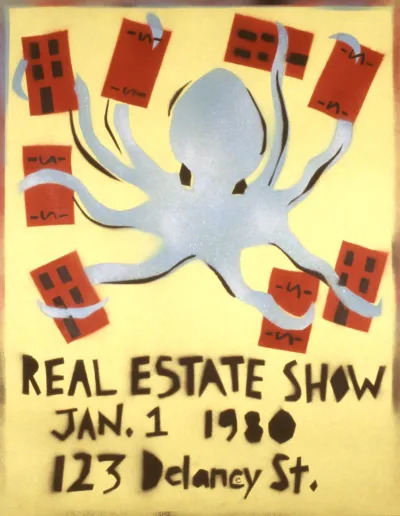

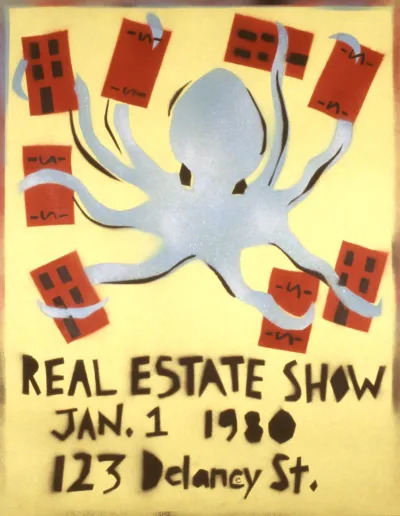

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist. The Pictures Generation wasn’t the only surge of baby boomer artists into late-1970s NYC. The same year Crimp mounted his show, a collection of artists formed Collaborative Projects Inc. (Colab), which promoted a raw, agitprop style that critiqued the sociopolitical circumstances of a recession-mired city left for dead. They had been conditioned by the same postwar American culture as their Pictures peers, yet their membership, which included Charlie and John Ahearn, Jane Dickson, Jenny Holzer, Rebecca Howland, Walter Robinson, and Kiki Smith among many others, tacked closer to Expressionism than to the cooler methodology promulgated by Crimp (though, in fact, Holzer and Robinson also overlapped with the Pictures crowd).

Colab used the tattered fabric of New York, mounting one-off exhibitions in vacated properties. These included “The Real Estate Show,” which was illegally installed (and quickly closed down by the NYPD) on New Year’s Day 1980 in an emptied building on the Lower East Side that the city had refused to rent to Colab, and more prominently, “The Times Square Show,” which debuted the following June in a shuttered massage parlor at West 41st Street and Seventh Avenue. In this respect, Colab operated in the spirit of Gordon Matta-Clark, whose site-specific installations in the early 1970s also used urban ruins like the deserted Pier 52 on Manhattan’s West Side.

Colab’s activism could also be seen as a carryover from the counterculture activism of the late 1960s, with Colab-adjacent spaces—Fashion Moda, ABC No Rio—respectively opening in the Bronx and on the Lower East Side in an attempt to reach out to communities of color. (Unfortunately, their good intentions—and for that matter, the entire downtown art world—would become stalking horses for gentrification.)

-

The Pictures Generation and Postmodernism

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © Richard Prince, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian. Photo: Owen Conway. Though Crimp’s show sounded the starting bell for the Pictures Generation, it was hardly determinative. His selections were necessarily limited and didn’t include the two artists—Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince—who would become the group’s biggest names. But the exhibition illustrated a new concept defining disciplines across the board: Postmodernism, which, in the case of art, undermined the modernist faith in stylistic progression. This was reflected, perhaps, in the variety of avenues the Pictures Generation explored.

The Pictures Generation and Performance

Robert Longo, Cindy, 1984 Artwork copyright © 2024 Robert Longo/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image copyright © Whitney Museum of American Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, New York. Certain members of the Pictures Generation brought over various genres from Postminimalism, most notably performance art. Matt Mullican, for example, would have himself hypnotized to produce works of art onstage, an approach that filtered Surrealism’s concept of automatic drawing through the acts seen on variety programs like The Ed Sullivan Show. Robert Longo mounted near-static tableaux operating in a kind of theater of stagecraft; one comprised a projection of a cinematic freeze-frame between live actions by an opera singer and a pair of men wrestling in slow motion on a rotating pedestal.

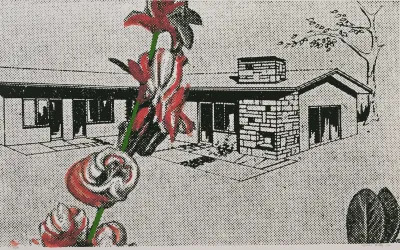

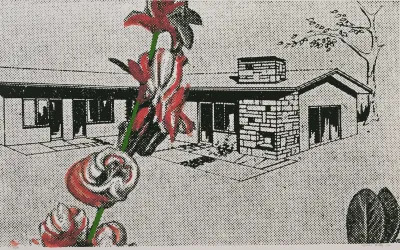

These artists also understood the way documentations of performance art divorced the genre from its kinetics. This schism had already been exploited by Photo-Conceptualists like William Wegman, whose photographs and videos depicted stupid pet tricks featuring his trusty Weimaraner, Man Ray. Following through, Laurie Simmons bridged the gap between Photo-Conceptualism and the Pictures aesthetic with scenes of toy housewives puttering around dollhouse ranch homes as a comment on suburban conformity.

Meanwhile, Longo also linked static artwork to performance with his “Men in the Cities,” a series of monumental charcoals based on photos of subjects having balls thrown at them: Twisting and turning, they were caught in poses responding to a violent act directed at them from outside the frame.

But the artist who most effectively crystallized performance as image was Cindy Sherman with her breakout photographic suite, “Untitled Film Stills.” In these photos she donned costumes and makeup to inhabit archetypical female roles from movies—ingenue, vamp, bombshell, innocent—that referenced not only Hollywood, but French New Wave and Italian neorealism as well. These images also alluded to the dress-up fantasies of girlhood and were derived from a sort of Method acting project in which Sherman came to her day job at Artists Space’s front desk attired as a 1950s secretary.

The Pictures Generation and Appropriation

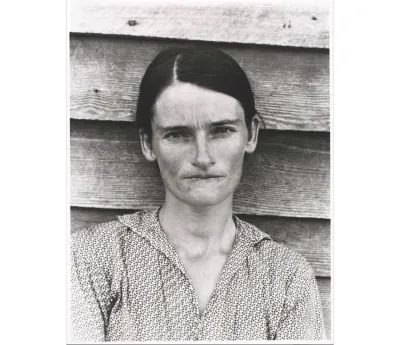

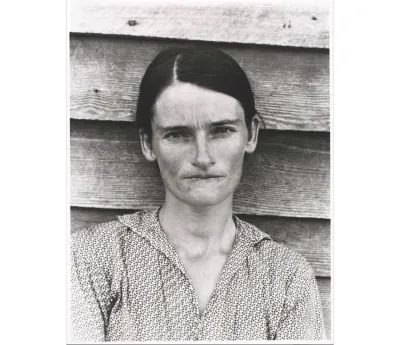

Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans: 4, 1981 Artwork copyright © Sherrie Levine. Walker Evans photograph copyright © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Digital image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Licensed by Art Resource, New York. Appropriation of imagery from the media was an essential tool of the Pictures Generation, though in a way that differed from how Pop artists borrowed from popular culture. Where Andy Warhol et al. saw an antidote to the self-seriousness of Abstract Expressionism, the Pictures Generation found ideological baggage.

As practiced by Pictures artists, appropriation often employed re-photography, a sort of doubling of the photographic image that reduced it to a sign and nothing more. Whether pursuing this specific methodology or not, the Pictures Generation’s use of appropriation generally fell into two interrelated categories: one in which imagery was set adrift from its original context; another in which it was shorn of its authorship.

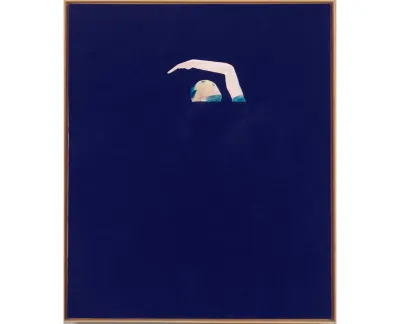

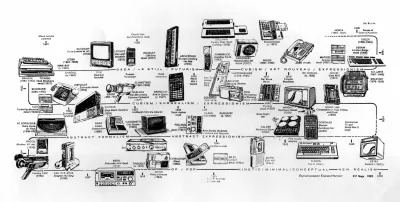

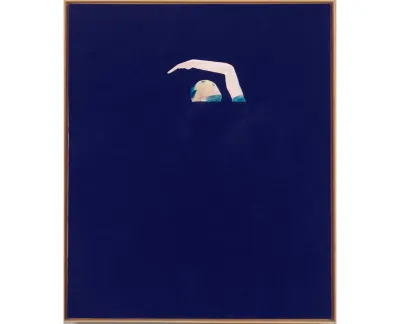

Examples of the former could be found in the work of Jack Goldstein, Troy Brauntuch, and Sarah Charlesworth. Born in 1945, Goldstein was the oldest participant in the “Pictures” show, an elder statesman whose practice highly influenced the rest of the Pictures Generation. In the mid 1970s he produced a series of film loops of various performative scenes (fencers fencing, a dog barking, the shimmering outline of a diver formed in lights as he leaps through the air) that, unlike the work of Sherman or Longo, were completely immune to readings. Later he produced paintings, many of which evoked the power of fury, whether in nature (lightning storms, volcano eruptions) or history (aerial bombardments during World War II). These compositions were largely airbrushed by an assistant, which not only separated them from Goldstein’s own subjectivity, but also imparted a sheen of impenetrability to evocations of the sublime.

Brauntuch explored the split between imagery and memory, creating ghostly white-on-black renderings on paper and canvas that seemed pregnant with meaning and yet totally opaque. Typically relying on archival photos of the Third Reich, these scenes detonated like time bombs of recognition once their source became apparent.

In her glossy photomontages, Charlesworth likewise devised methods of distancing her subjects from the viewer by isolating silhouetted cutouts from magazines on bright-hued monochrome fields mounted in color-matching frames. She frequently paired images, as in one instance where a 1940s evening gown was juxtaposed with a prone woman mummified in S&M bondage gear—a piquant apposition of Hollywood glamor and fetishism. Her work deconstructed the exigencies of desire, whether it involved sexuality, spirituality, or mass consumption.

At the same time, certain Pictures Generation members, notably Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine, took appropriation to a new level, turning it into both genre and subject. Eschewing artistic embellishment, these artists presented iterations of images that were unchanged, identifiable—and even copyrighted—as their own.

The groundwork for their efforts was laid by Roland Barthes, whose 1967 essay The Death of the Author posited that interpretations of text shouldn’t be based on the writer’s intentions but rather on individual readers’ interpretation of the work. But Barthes’s catchy title was soon taken literally, and in the art world in particular, Douglas Crimp’s idea of liberating representation from the represented was soon taken to mean usurping its ownership as well. Both Prince and Levine pushed the envelope on that score.

During the 1970s, Prince had worked at Time Inc., where he filed advertising tear sheets. Though he’d been working in a mode resembling Abstract Expressionism, his job inspired his huge leap into repurposing such images, with no frame of reference beyond their appearance as an artifact. Unlike Warhol and his use of silkscreened half-tones, Prince made no evident connection between his source material and its new iteration. Rather, he presented the original as it was, except for the fact that it was now a photograph instead of a page torn out of a magazine. Starting with a series of wristwatch ads featuring male models, he eventually created his signature borrowings of the iconic cowboy used to sell Marlboro cigarettes. As in the case of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup cans, this image became as closely associated with Prince as it was with the product.

For her part, Levine mined 20th-century art history, leveraging its milestones in a manner similar to Prince’s treatment of the Marlboro Man. But unlike Prince’s work, which celebrated machismo while pretending to undermine it, Levine’s could be seen as a feminist jape at modernism’s masculine self-aggrandizement. Her most notorious series, “After Walker Evans,” usurped the famed photographer’s Depression-era images, revealing the exploitative subtext of its sociological intentions.

The Pictures Generation and Text

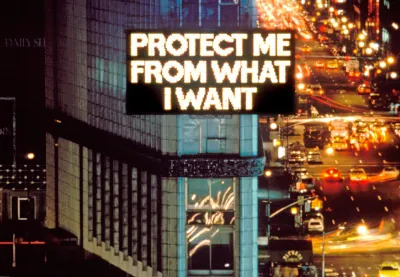

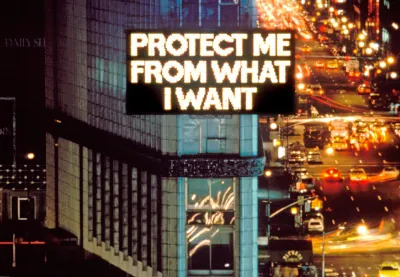

Jenny Holzer, from Survival (1983-85), 1985 Artwork copyright © 2024 Jenny Holzer/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image courtesy of Jenny Holzer/Art Resource, New York. The use of text as the focal point of objects, if not an outright substitution for them, was a hallmark of Conceptualism that was carried over into the practices of Pictures Generation artists, most conspicuously Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. Neither shared the rage for dematerializing art, however, choosing instead to explore the role of text in fostering mass consumption. This largely meant advertising, of course, but Holzer and Kruger weren’t interested in ads, per se, but rather in the strategies of persuasion behind them. Both artists parodied the semiotics of authority by adopting a fictive voice meant to mimic the mechanics of messaging—splitting, once again, representation from what it was meant to represent.

True to the practices of Colab, Holzer, for example, posted flyers around Lower Manhattan bearing inflammatory aphorisms (such as “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT”) that she dubbed “Truisms.” These would become further reified as animated LED signboards and other objects.

Meanwhile, Kruger amalgamated stock photos, words, and punchy graphics to offer meta-textual commentaries on the zeitgeist. For such signature works as Untitled (I shop therefore I am), which featured a hand holding a card printed with the eponymous slogan, she drew on her tenure as art director for Mademoiselle magazine. But instead of stimulating consumer appetites, Kruger used her skills to expose the corrupting influence of late capitalism (though the latter would have the last laugh as her style was lifted to sell stuff).

Abstraction as Image

Allan McCollum, Collection of Forty Plaster Surrogates, 1982 (cast and painted in 1984) Artwork copyight © Allan McCollum, courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York. Somewhat counterintuitively to the undermining of representation, two artists, Allan McCollum and James Welling, invested abstraction with pictorial attributes, turning it into another form of imagery—which is indeed how it exists in reproduction. Welling created black-and-white photos, for instance, featuring closeups of crinkled aluminum foil, or draped dark fabrics with white flakes collecting in their folds. McCollum, for his part, cast seemingly infinite permutations of the same small plaster relief sculpture: a black rectangle surrounded by bands suggesting a mat and picture frame; in essence, McCollum was compressing the preconception of what an art object resembles to its component parts.

The Pictures Generation and Painting

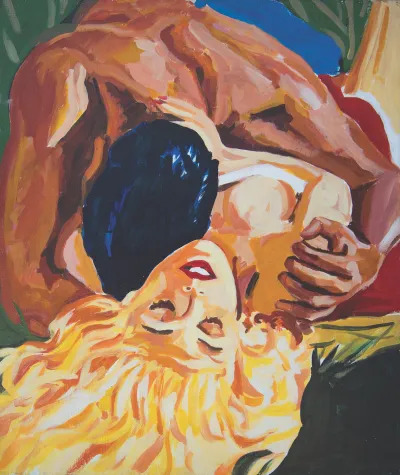

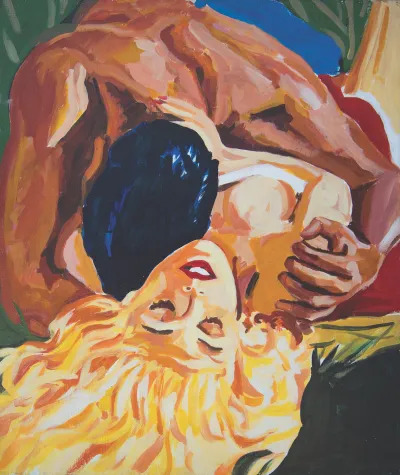

Walter Robinson, The Eager Ones, 1979 Courtesy of the artist. Though the work of the Pictures Generation was often grounded in photography, some of its members pursued painting, the most salient being David Salle. Salle initially worked in a Photo-Conceptualist mode (creating, for instance, a series of women staring out of kitchen windows while holding cups of instant coffee whose jar labels were pasted below). But later he turned to limning evanescent compositions in which outlines of random images floated over others rendered in more complete tonalities—a trope whose lineage went back through Sigmar Polke to the late paintings of Francis Picabia. Salle combined material taken from snapshots, cartoons, and art history into ever more baroque aggregations of pictorial stuff infused with a mean misogynistic streak. Salle soon became one of the names synonymous with the Neo-Expressionists, who followed on the heels of the Pictures Generation.

More consistent with the Pictures tactics perhaps, was another Colab associate, Walter Robinson. Basically a self-taught painter (he’d studied philosophy in college), Robinson became known for appropriating the lurid covers of mid-century pulp-fiction paperbacks, painting them as they’d originally been before the addition of text.

-

The Pictures Generation Legacy

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Magenta Plains, New York. Within just a few years of the “Pictures” show, New York’s art world was inundated with artists pursuing a wide range of representational techniques that brought them acclaim and money while burying the exhibition’s theoretical premise. Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example, harnessed the populist spirit of graffiti to great success, making street art safe for collectors. The aforementioned Neo-Expressionists (which, besides Salle, counted Eric Fischl, Julian Schnabel, and Francesco Clemente within its ranks) revived the macho posture, if not the angst, of AbEx.

But the Pictures aesthetic continued to reverberate within the work of succeeding artists. A second-generation wave of Pictures-inspired names—Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw, and John Miller—came out of CalArts, while artist-run galleries in the East Village such as Nature Morte, International With Monument, Cash/Newhouse, and Jay Gorney Modern Art promoted a kind of Pictures 2.0 sensibility, as seen in the work of Peter Nagy, Alan Belcher, Gretchen Bender, and others.

These East Village venues provided a haven for original Pictures artists (Prince, Levine), whose work didn’t initially mint money, and also birthed a new kind of appropriation involving consumer objects instead of imagery. Called commodity fetishism, this approach was associated with the likes of Haim Steinbach and Ashley Bickerton and would soon be rolled into another term, Neo-Geo, which was marketed as a reaction to Neo-Expressionism.

Needless to say, defining the impact of any group of artists at a particular point in time has its limits, especially when it comes to the Pictures Generation. What can arguably be said about these artists is that they were there at the exact instant when an ideational dam holding the waters of modernist ideology for a century broke open. The flood that resulted overwhelmed the distinction between high and low culture, as artists were hailed as the new rock stars, and money became a bigger attraction in the public imagination than the objects collectors chased around galleries and auction houses. Given the torrent, modernism’s history as previously written was no longer adequate to define art’s value, leaving the invisible hand of market forces to sort it out.

Who Were the Artists of the Pictures Generation?

As the moniker implies, the term Pictures Generation (which also included Sarah Charlesworth, Barbara Kruger, Allan McCollum, Matt Mullican, Richard Prince, Walter Robinson, Cindy Sherman, David Salle, Laurie Simmons, James Welling, and a host of others) didn’t denote a style so much as it signaled the advent of a cohort born during America’s postwar baby boom. (They weren’t alone, but more on that later.) They ascended alongside the political forces that would ultimately yield the Reagan revolution, which dismantled the liberal, New Deal order, and while any direct correlation with the Pictures Generation is debatable, its members did manage to reshape the art world largely thanks to Reagan’s reconfiguration of America.

A Watershed Moment

The Pictures Generation arrived at a time when New York was still considered the center of artistic production, and artists—and especially critics—still clung to the idea of pushing creative boundaries much as they had throughout the breakthroughs of 20th-century modernism. Both notions would be derailed by an art market spurred on by tax cuts and a resurgent Wall Street under Reagan. While rising and falling over the following 50 years, this boom would ultimately morph into a globalized entity wherein market success, rather than critically sanctioned stylistic progress, determined important art.

As one of the first groups of artists to benefit from this economic largesse, the Pictures Generation arguably initiated a chain of causality that eventually resulted in the ahistorical character of contemporary art today. Nobody, not least the Pictures Generation, could foresee the developments to come, but in retrospect, one could trace them back to that moment in the fall of 1977.

The 1970s New York Art World

New York’s art scene during the 1970s was conditioned by the same economic travails afflicting the city, though not entirely for the worse. As much as NYC’s deindustrialization may have been a bane to its citizenry, it proved to be a boon to artists thanks mainly to collapsing rents that produced cheap studio space, especially in the empty lofts of lower Manhattan.

NYC’s financial implosion was echoed by a concomitant chill in the art market following the buoyant buying of the early to mid 1960s, when Pop Art, and to a lesser extent Minimalism, excited collectors looking for alternatives to Abstract Expressionism. Yet the low cost of living and the presence of alternative, taxpayer-funded showcases like the one that hosted “Pictures” permitted a sense of creative freedom among many artists, giving them the luxury of rejecting the commercial gallery system.

During the late 1960s and early ’70s, this attitude sparked a decentered and dematerialized practice that emphasized idea over form, leading to new genres such as Conceptualism, earthworks, installation/process art, video art, and performance. To distinguish them from Minimalism (which, while largely sculptural and highly finished, was no less reductive), these approaches were lumped under the umbrella term Postminimalism, setting the stage for a radical endgame in which art reached a kind of degree zero of pure discourse.

This notion was as nihilistic as it was liberating, however, so as the decade wore on, the search for a way out of the strictures of Postminimalism began. Eclecticism became an art-world buzzword, but there was still a desire for a return to a more viewer-friendly and concrete expression that would comport with the narrative Postminimalism had fashioned for itself—a longing that “Pictures” aimed to address.

The “Pictures” Show

“Pictures” signaled a return to representationalism, though the latter had hardly disappeared, even during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. Scores of artists (Barkley Hendricks, Alex Katz, Catherine Murphy, Alice Neel, Philip Pearlstein, Fairfield Porter, and Bob Thompson, to name just a few) worked in a diverse spectrum of figurative styles ranging from expressionistic to realistic. Moreover, Pop Art and photorealism served as antecedents for the Pictures Generation—the former because it gathered motifs from mass culture, the latter because it mediated painting and sculpture through the prism of photography.

The “Pictures” exhibition, however, framed its premise within the context of Conceptualism. Just as Conceptual Art severed object and idea, “Pictures” attempted to separate representation “from the tyranny of the represented,” as show organizer Douglas Crimp put it. This paradoxical assertion cloaked a reaction against Postminimalism in its own tenets, but Crimp’s argument was also rooted in the broader context in which the Pictures artists had come of age.

The Postwar Roots of the Pictures Generation

Pictures Generation artists came largely from white, middle-class backgrounds, growing up in the suburbs within a media monoculture comprising a limited array of broadcast television channels (most cities had only three). From childhood onward, they were exposed to a diet of sitcoms, Westerns, and police procedurals that reinforced white male privilege. Postwar television also instantaneously relayed news on monumental events such as the civil rights movement, the Kennedy assassinations, and the Vietnam War, delivering shocks to the system that helped to fray the societal norms coming out of World War II. In a way barely conceivable today, television had the power to tie the country together—and to break it apart as well. This underlying tension was mirrored within the Pictures aesthetic.

Television, along with Hollywood films, glossy magazines, and the blandishments of Madison Avenue, produced a pervasive landscape of memes far more lasting than those generated online today. It’s often said that the members of the Pictures Generation were the first artists to have grown up with television; this meant that they were the first to know life as a wholly manufactured phenomenon designed to stimulate consumerism, making their experience a kind of late-capitalist irreality—a “tyranny of the represented,” per Crimp. The Pictures Generation’s shaping by mass media was far more cohesive and top-down than it is for the young of today and also different from the enculturation of older Pop artists, like Andy Warhol (born in 1928), who viewed popular culture as a smorgasbord of subjects rather than as a totalizing regime.

The Return of Representationalism in the 1970s

As previously noted, artists continued to pursue representational art in different ways throughout the postwar period, though there were several epiphenomenal feints in the direction of its resurgence that presaged “Pictures” within 1970s art.

For example, much as Jasper Johns did with his targets and flags, the Pattern and Decoration (P&D) movement (whose adherents included Tina Girouard, Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, and Miriam Schapiro) attempted to split the difference between the recognizable and the abstract by employing repetitive motifs derived from textiles and wallpaper. At the same time, feminist artists sustained representationalism as they attacked traditional depictions of women through painting (Judy Chicago, Joan Semmel), body art (Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke) and other genres.

Representationalism hadn’t completely disappeared within Postminimalism either. The otherwise ephemeral manifestations of performance art were documented in photographs and videos that became de facto figurative artworks. This practice almost immediately spun off into Photo-Conceptualism, a form separate from the recording of actions staged for an audience. Artists such as William Wegman and, more influentially for the Pictures Generation, John Baldessari, often used color film and serial imagery to produce works that were likewise representational, and artists utilizing video as a discrete genre did the same.

Yet another subset of Postminimalists—Sol Lewitt, Mel Bochner, and Dorothea Rockburne, among others—had been applying epistemological systems (linguistics, mathematics) to abstract paintings and sculptures, but here, too, certain artists managed to sneak representation into the mix. Jonathan Borofsky’s drawings, sculptures, and installations were taken from dreams, but he also framed them within a conceit of counting toward infinity so that each object was numbered according to its appearance in the scheme. Far more obscure was the work of Pinchas Cohen Gan, an Israeli-Moroccan artist living in New York who abandoned strict Conceptualism by introducing an enigmatic, everyman figure into paintings done on tablecloths; sketchy and minimalistic, these compositions formulated art as a kind of science. Jennifer Bartlett arranged panels within grids that featured content algorithmically advancing from geometric shapes to renderings, for example, of landscapes resembling eight-bit computer graphics.

Elsewhere, Minimalist sculptor Joel Shapiro deviated from the non-referential, specific object template of Donald Judd and Dan Flavin by scattering small, house-shaped objects within sprawling installations, while Robert Moskowitz plunked isolated silhouettes of Cadillac tail fins and Chicago’s Wrigley Building into allover fields of gestural marks. Other echoes of Postminimalism—textualization, process art—found their way into the figurative paintings of Neil Jenney and Joe Zucker.

By 1977, then, a renewal of representational art was very much in the air, though it took “Pictures” to attempt a cohesive theory of the case. A year later, more-established venues tried something similar, with the Whitney and the New Museum mounting exhibitions respectively titled “New Image Painting” and “‘Bad’ Painting” though neither included artists from the Pictures Generation.

The European Influence on the Pictures Generation

Aside from the dynamics of postwar America in which they’d come of age, the Pictures Generation was very much impacted by contemporaneous currents in Europe, especially the New Wave cinema and critical writings coming out of France.

Filmmakers such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, and Claude Chabrol rejected the polished look of studio productions, using lightweight cameras and spontaneous cinematography to give their movies the feel of documentary realism. They subverted conventional montage with edits that disrupted narrative flow. The look of these films, and the meta-commentaries they often made on Hollywood genres such as film noir, became touchstones for several artists from the Pictures Generation.

Just as pertinent were the theoretical musings of the French philosophes who arose during the sociopolitical clamor of May 1968—among them Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, and Jean Baudrillard. Their texts, though highly varied, interrogated the articulation of meaning itself, positing that it was governed—and was a function of—institutional power. These ideas, labelled Poststructuralism by American academics, resonated with the Pictures Generation’s ironic realization that the formative years of its members had been an existential immersion into artifice.

The Pictures Generation was also aware of the work in Germany of Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, who had hatched a kind of tongue-in-cheek movement they dubbed Capitalist Realism. This, too, was aimed at the “tyranny of the represented” seen in the projection of American pop culture across the Continent as a form of soft power during the Cold War.

The Pictures Generation Arrives

The Pictures Generation distinguished itself from previous schools in other ways as well. Women artists—Sarah Charlesworth, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman, and Laurie Simmons among them—played a significant role, injecting a strain of feminism into the Pictures sensibility, albeit one that was less interested in female empowerment than in unpacking the ways in which images of women were exploited to foster consumption. (Interestingly, if somewhat predictably, the larger visibility of women artists within the Pictures Generation was met by a backlash from some of their male peers.)

Migration to New York had always been a feature of the city’s art scene; artists from all over the country and world came there to find their stylistic footing. But here, too, the Pictures Generation differentiated itself to a certain degree, as some members shared specific points of origin that forged their sensibilities outside NYC. Several of them—Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Matt Mullican, David Salle, and James Welling—had graduated from the California Institute for the Arts (CalArts), of which John Baldessari had been a founding faculty member. Then there was the so-called Buffalo Invasion, which included Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo among its ranks. All graduates of the State University of New York at Buffalo, they had coalesced around a regional alternative space called Hallwalls before coming to New York.

Pictures Generation Peers

The Pictures Generation wasn’t the only surge of baby boomer artists into late-1970s NYC. The same year Crimp mounted his show, a collection of artists formed Collaborative Projects Inc. (Colab), which promoted a raw, agitprop style that critiqued the sociopolitical circumstances of a recession-mired city left for dead. They had been conditioned by the same postwar American culture as their Pictures peers, yet their membership, which included Charlie and John Ahearn, Jane Dickson, Jenny Holzer, Rebecca Howland, Walter Robinson, and Kiki Smith among many others, tacked closer to Expressionism than to the cooler methodology promulgated by Crimp (though, in fact, Holzer and Robinson also overlapped with the Pictures crowd).

Colab used the tattered fabric of New York, mounting one-off exhibitions in vacated properties. These included “The Real Estate Show,” which was illegally installed (and quickly closed down by the NYPD) on New Year’s Day 1980 in an emptied building on the Lower East Side that the city had refused to rent to Colab, and more prominently, “The Times Square Show,” which debuted the following June in a shuttered massage parlor at West 41st Street and Seventh Avenue. In this respect, Colab operated in the spirit of Gordon Matta-Clark, whose site-specific installations in the early 1970s also used urban ruins like the deserted Pier 52 on Manhattan’s West Side.

Colab’s activism could also be seen as a carryover from the counterculture activism of the late 1960s, with Colab-adjacent spaces—Fashion Moda, ABC No Rio—respectively opening in the Bronx and on the Lower East Side in an attempt to reach out to communities of color. (Unfortunately, their good intentions—and for that matter, the entire downtown art world—would become stalking horses for gentrification.)

The Pictures Generation and Postmodernism

Though Crimp’s show sounded the starting bell for the Pictures Generation, it was hardly determinative. His selections were necessarily limited and didn’t include the two artists—Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince—who would become the group’s biggest names. But the exhibition illustrated a new concept defining disciplines across the board: Postmodernism, which, in the case of art, undermined the modernist faith in stylistic progression. This was reflected, perhaps, in the variety of avenues the Pictures Generation explored.

The Pictures Generation and Performance

Certain members of the Pictures Generation brought over various genres from Postminimalism, most notably performance art. Matt Mullican, for example, would have himself hypnotized to produce works of art onstage, an approach that filtered Surrealism’s concept of automatic drawing through the acts seen on variety programs like The Ed Sullivan Show. Robert Longo mounted near-static tableaux operating in a kind of theater of stagecraft; one comprised a projection of a cinematic freeze-frame between live actions by an opera singer and a pair of men wrestling in slow motion on a rotating pedestal.

These artists also understood the way documentations of performance art divorced the genre from its kinetics. This schism had already been exploited by Photo-Conceptualists like William Wegman, whose photographs and videos depicted stupid pet tricks featuring his trusty Weimaraner, Man Ray. Following through, Laurie Simmons bridged the gap between Photo-Conceptualism and the Pictures aesthetic with scenes of toy housewives puttering around dollhouse ranch homes as a comment on suburban conformity.

Meanwhile, Longo also linked static artwork to performance with his “Men in the Cities,” a series of monumental charcoals based on photos of subjects having balls thrown at them: Twisting and turning, they were caught in poses responding to a violent act directed at them from outside the frame.

But the artist who most effectively crystallized performance as image was Cindy Sherman with her breakout photographic suite, “Untitled Film Stills.” In these photos she donned costumes and makeup to inhabit archetypical female roles from movies—ingenue, vamp, bombshell, innocent—that referenced not only Hollywood, but French New Wave and Italian neorealism as well. These images also alluded to the dress-up fantasies of girlhood and were derived from a sort of Method acting project in which Sherman came to her day job at Artists Space’s front desk attired as a 1950s secretary.

The Pictures Generation and Appropriation

Appropriation of imagery from the media was an essential tool of the Pictures Generation, though in a way that differed from how Pop artists borrowed from popular culture. Where Andy Warhol et al. saw an antidote to the self-seriousness of Abstract Expressionism, the Pictures Generation found ideological baggage.

As practiced by Pictures artists, appropriation often employed re-photography, a sort of doubling of the photographic image that reduced it to a sign and nothing more. Whether pursuing this specific methodology or not, the Pictures Generation’s use of appropriation generally fell into two interrelated categories: one in which imagery was set adrift from its original context; another in which it was shorn of its authorship.

Examples of the former could be found in the work of Jack Goldstein, Troy Brauntuch, and Sarah Charlesworth. Born in 1945, Goldstein was the oldest participant in the “Pictures” show, an elder statesman whose practice highly influenced the rest of the Pictures Generation. In the mid 1970s he produced a series of film loops of various performative scenes (fencers fencing, a dog barking, the shimmering outline of a diver formed in lights as he leaps through the air) that, unlike the work of Sherman or Longo, were completely immune to readings. Later he produced paintings, many of which evoked the power of fury, whether in nature (lightning storms, volcano eruptions) or history (aerial bombardments during World War II). These compositions were largely airbrushed by an assistant, which not only separated them from Goldstein’s own subjectivity, but also imparted a sheen of impenetrability to evocations of the sublime.

Brauntuch explored the split between imagery and memory, creating ghostly white-on-black renderings on paper and canvas that seemed pregnant with meaning and yet totally opaque. Typically relying on archival photos of the Third Reich, these scenes detonated like time bombs of recognition once their source became apparent.

In her glossy photomontages, Charlesworth likewise devised methods of distancing her subjects from the viewer by isolating silhouetted cutouts from magazines on bright-hued monochrome fields mounted in color-matching frames. She frequently paired images, as in one instance where a 1940s evening gown was juxtaposed with a prone woman mummified in S&M bondage gear—a piquant apposition of Hollywood glamor and fetishism. Her work deconstructed the exigencies of desire, whether it involved sexuality, spirituality, or mass consumption.

At the same time, certain Pictures Generation members, notably Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine, took appropriation to a new level, turning it into both genre and subject. Eschewing artistic embellishment, these artists presented iterations of images that were unchanged, identifiable—and even copyrighted—as their own.

The groundwork for their efforts was laid by Roland Barthes, whose 1967 essay The Death of the Author posited that interpretations of text shouldn’t be based on the writer’s intentions but rather on individual readers’ interpretation of the work. But Barthes’s catchy title was soon taken literally, and in the art world in particular, Douglas Crimp’s idea of liberating representation from the represented was soon taken to mean usurping its ownership as well. Both Prince and Levine pushed the envelope on that score.

During the 1970s, Prince had worked at Time Inc., where he filed advertising tear sheets. Though he’d been working in a mode resembling Abstract Expressionism, his job inspired his huge leap into repurposing such images, with no frame of reference beyond their appearance as an artifact. Unlike Warhol and his use of silkscreened half-tones, Prince made no evident connection between his source material and its new iteration. Rather, he presented the original as it was, except for the fact that it was now a photograph instead of a page torn out of a magazine. Starting with a series of wristwatch ads featuring male models, he eventually created his signature borrowings of the iconic cowboy used to sell Marlboro cigarettes. As in the case of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup cans, this image became as closely associated with Prince as it was with the product.

For her part, Levine mined 20th-century art history, leveraging its milestones in a manner similar to Prince’s treatment of the Marlboro Man. But unlike Prince’s work, which celebrated machismo while pretending to undermine it, Levine’s could be seen as a feminist jape at modernism’s masculine self-aggrandizement. Her most notorious series, “After Walker Evans,” usurped the famed photographer’s Depression-era images, revealing the exploitative subtext of its sociological intentions.

The Pictures Generation and Text

The use of text as the focal point of objects, if not an outright substitution for them, was a hallmark of Conceptualism that was carried over into the practices of Pictures Generation artists, most conspicuously Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. Neither shared the rage for dematerializing art, however, choosing instead to explore the role of text in fostering mass consumption. This largely meant advertising, of course, but Holzer and Kruger weren’t interested in ads, per se, but rather in the strategies of persuasion behind them. Both artists parodied the semiotics of authority by adopting a fictive voice meant to mimic the mechanics of messaging—splitting, once again, representation from what it was meant to represent.

True to the practices of Colab, Holzer, for example, posted flyers around Lower Manhattan bearing inflammatory aphorisms (such as “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT”) that she dubbed “Truisms.” These would become further reified as animated LED signboards and other objects.

Meanwhile, Kruger amalgamated stock photos, words, and punchy graphics to offer meta-textual commentaries on the zeitgeist. For such signature works as Untitled (I shop therefore I am), which featured a hand holding a card printed with the eponymous slogan, she drew on her tenure as art director for Mademoiselle magazine. But instead of stimulating consumer appetites, Kruger used her skills to expose the corrupting influence of late capitalism (though the latter would have the last laugh as her style was lifted to sell stuff).

Abstraction as Image

Somewhat counterintuitively to the undermining of representation, two artists, Allan McCollum and James Welling, invested abstraction with pictorial attributes, turning it into another form of imagery—which is indeed how it exists in reproduction. Welling created black-and-white photos, for instance, featuring closeups of crinkled aluminum foil, or draped dark fabrics with white flakes collecting in their folds. McCollum, for his part, cast seemingly infinite permutations of the same small plaster relief sculpture: a black rectangle surrounded by bands suggesting a mat and picture frame; in essence, McCollum was compressing the preconception of what an art object resembles to its component parts.

The Pictures Generation and Painting

Though the work of the Pictures Generation was often grounded in photography, some of its members pursued painting, the most salient being David Salle. Salle initially worked in a Photo-Conceptualist mode (creating, for instance, a series of women staring out of kitchen windows while holding cups of instant coffee whose jar labels were pasted below). But later he turned to limning evanescent compositions in which outlines of random images floated over others rendered in more complete tonalities—a trope whose lineage went back through Sigmar Polke to the late paintings of Francis Picabia. Salle combined material taken from snapshots, cartoons, and art history into ever more baroque aggregations of pictorial stuff infused with a mean misogynistic streak. Salle soon became one of the names synonymous with the Neo-Expressionists, who followed on the heels of the Pictures Generation.

More consistent with the Pictures tactics perhaps, was another Colab associate, Walter Robinson. Basically a self-taught painter (he’d studied philosophy in college), Robinson became known for appropriating the lurid covers of mid-century pulp-fiction paperbacks, painting them as they’d originally been before the addition of text.

The Pictures Generation Legacy

Within just a few years of the “Pictures” show, New York’s art world was inundated with artists pursuing a wide range of representational techniques that brought them acclaim and money while burying the exhibition’s theoretical premise. Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example, harnessed the populist spirit of graffiti to great success, making street art safe for collectors. The aforementioned Neo-Expressionists (which, besides Salle, counted Eric Fischl, Julian Schnabel, and Francesco Clemente within its ranks) revived the macho posture, if not the angst, of AbEx.

But the Pictures aesthetic continued to reverberate within the work of succeeding artists. A second-generation wave of Pictures-inspired names—Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw, and John Miller—came out of CalArts, while artist-run galleries in the East Village such as Nature Morte, International With Monument, Cash/Newhouse, and Jay Gorney Modern Art promoted a kind of Pictures 2.0 sensibility, as seen in the work of Peter Nagy, Alan Belcher, Gretchen Bender, and others.

These East Village venues provided a haven for original Pictures artists (Prince, Levine), whose work didn’t initially mint money, and also birthed a new kind of appropriation involving consumer objects instead of imagery. Called commodity fetishism, this approach was associated with the likes of Haim Steinbach and Ashley Bickerton and would soon be rolled into another term, Neo-Geo, which was marketed as a reaction to Neo-Expressionism.

Needless to say, defining the impact of any group of artists at a particular point in time has its limits, especially when it comes to the Pictures Generation. What can arguably be said about these artists is that they were there at the exact instant when an ideational dam holding the waters of modernist ideology for a century broke open. The flood that resulted overwhelmed the distinction between high and low culture, as artists were hailed as the new rock stars, and money became a bigger attraction in the public imagination than the objects collectors chased around galleries and auction houses. Given the torrent, modernism’s history as previously written was no longer adequate to define art’s value, leaving the invisible hand of market forces to sort it out.

The Thriving Jazz Club in the Heart of Sleepy California Wine Country

Shopping Early for a Luxe Advent Calendar? One of Australia’s Favorite Fragrance Houses Has You Covered

Savannah Bananas Look for Their Own Mr. October