In 2017, Gerhard Richter announced that he’d completed the last of his paintings, prompting some to say that he was retiring altogether. This wasn’t the case; he continued to produce drawings, other works on paper, and even sculpture. Recently unveiled examples completed in 2022 suggest that he had simply turned his attention to work that was more modestly scaled and less arduous to produce than the full-size canvases for which he’d become known—understandable, given that he’s now 93. All the same, the change was astonishing for someone whose 60-year commitment to the medium of paint is summed up by the title of his book of philosophical musings: The Daily Practice of Painting.

Still, one could argue that Richter, as the greatest living artist of the postwar era, had nothing left to prove. That much will certainly be made clear in a massive Richter retrospective opening this month at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. Comprising some 250 objects, it is the largest survey of his work to date, exceeding MoMA’s landmark Richter show in 2002.

“My paintings are wiser than I am,” Richter once said. To be sure, his work has judiciously distilled, as no other postwar oeuvre has, the dialectic between violence and culture that’s marked the 20th century. But he may be too modest: As a German artist who’s lived through Hitler, Communism, the Cold War, and the fall of the Berlin Wall, he’s been acutely attuned to the deleterious effects of ideology on art.

Spanning mediums that include sculpture and photography as well as painting, Richter’s pieces number in the thousands, jumping between abstraction (both minimalist and expressionistic) and elusive, photo-based representations ranging from grainy newspaper imagery to natural vistas worthy of the German Romanticist painter Caspar David Friedrich.

This multifarious approach could be construed as evidence of a profound suspicion of singular aesthetic strategies, leading many to complain that his efforts look like they were done by multiple artists. Richter, however, has managed the neat trick of conjuring a signature style out of a plethora of them.

The resulting cerebral whole has struck some as too chilly and devoid of feeling. But this misses the point Richter has been making throughout his career: that feeling is vulnerable to the numbing effects of historical trauma, which in turn casts doubt on the efficacy of art.

-

Early life

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). Gerhard Richter was born the first child of Horst and Hildegard Richter in Dresden, Germany, a year before Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 (a sister, Gisela, was four years his junior). His father was a secondary school teacher and his mother a bookseller who played piano. In 1935 Horst moved the family to Reichenau, in present-day Poland, to accept a job there. At the outbreak of World War II, in 1939, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht, eventually becoming an Allied POW held captive until the war’s end. Released in 1946, he returned to his family, which in his absence had relocated to a village near the Czech border called Waltersdorf.

Horst had been compelled to join the Nazi Party to find work within the Third Reich’s educational system, and even then he’d had to settle for a post in a provincial backwater. This turned out be advantageous for Richter’s family, as Reichenau’s rural isolation insulated them from the prying eyes of the Gestapo and, early on at least, from the ravages of the war. Indeed, Richter recalled family life as “simple, orderly, structured—mother playing the piano and father earning money.”

But like the lives of all Germans at the time, Richter’s childhood was deformed by Hitler’s regime. Upon turning 10, he was required to join the Deutsche Jungvolk—the junior branch of the Hitler Youth—while the war exacted a personal cost on his family. Two of his uncles died at the front, including one, Rudi, who was immortalized in one of Richter’s blurred, monochromatic paintings from the mid-1960s (more to come on these as well). He likewise commemorated his aunt Marianne, who suffered from schizophrenia. Per Nazi policy, she was forcibly sterilized and committed to a psychiatric hospital. There she was starved to death as part of the Reich’s notorious T4 euthanasia program, which systematically murdered the disabled because they were deemed unworthy of life. She was dumped in a mass grave along with 8,000 other T4 victims.

More chillingly, Richter’s future father-in-law, Heinrich Eufinger, was an SS doctor assigned to the same hospital where Marianne was confined to administer sterilization procedures like the one performed on her—which he may have carried out, though that remains unproved. Eufinger appears in Richter’s Family at the Seaside (1964), smiling alongside his wife and children.

Richter was unaware of these details when he painted Marianne in 1965, as a portrait taken form a snapshot of himself as an infant sitting on her lap when she was 14. He found out only after the journalist Jürgen Schreiber uncovered the facts for his 2005 biography of Richter, Ein Maler aus Deutschland (A Painter from Germany). Still, when Richter was a boy, Marianne was treated as a cautionary figure, with his mother discouraging him from trouble by saying, “Don’t do that or you’ll end up like Aunt Marianne.”

Richter’s hometown of Dresden was devasted by Britain’s RAF in February 1945. While not present at the time, Richter was deeply affected by its destruction, and the bombing, too, would find its way into his work—most explicitly in 14. Feb. 45 (2002), an appropriated and retouched aerial reconnaissance photo of the ruined city of Cologne (bombed on the same day as Dresden) that testifies to how it still haunted him six decades later.

At the war’s end Richter’s family found themselves inside the Soviet occupation zone, which became Communist East Germany, a rump nation where one totalitarian regime was exchanged for another. Richter would remain there until his escape West in 1961.

-

Education

Image Credit: Rob Welham/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. Thanks to his mother, Richter was exposed to monographs on Velázquez, Dürer, and the German Impressionist-cum-Expressionist, Lovis Corinth. He began drawing, and at age 15, in 1947, started to attend evening classes in painting while studying bookkeeping. A year later, he secured an apprenticeship at a company that produced banners for the East German government.

In 1950 Richter became a set painter for a theater, which eventually fired him for refusing to create a mural for its stairwell. Shortly thereafter, he applied to the Dresden Art Academy to study painting but was initially rejected. For the next eight months, he worked at a textile plant until finally gaining acceptance to the academy in 1951.

The Dresden Richter returned to was in ruins, with piles of rubble strewn along his way to class. The art academy, which had been damaged by Allied bombing but remained largely intact, emphasized Socialist Realism, the Soviet Union’s official style under Stalin. Luckily, Richter’s instructor, Heinz Lohmar, was relatively lenient about imposing the Socialist Realist line.

Richter kept in touch with developments in the West thanks to an aunt in West Germany who sent him books and periodicals on art and photography. Travel between the two Germanies was easier before the Berlin Wall was erected, and Richter took several trips to West Berlin, authorized by Lohmar, to experience the latest in Western film, theater, and art—which, along with Richter’s exposure to Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings at Dresden’s Pillnitz Castle museum, planted the seeds of his future work.

After graduating from the academy, Richter received several commissions as a mural painter. He could have easily continued down that path, but in 1959 he traveled West to Kassel for Documenta II, an international art exposition where he discovered Jackson Pollock, Jean Fautrier, and Lucio Fontana. It proved to be a pivotal moment, and in April 1961, shortly before the Berlin Wall went up, he and his first wife, Ema, defected.

-

Postwar West Germany

Image Credit: Photograph copyright © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of the Gerhard Richter Archive, Dresden. In 1963 Richter and Leug traveled to Paris to see an exhibition by the American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. They’d already been aware of Pop Art through art magazines, and while making their way around Paris’s galleries they introduced themselves as German Pop artists. The Capitalist Realism label was later coined by Richter in a letter sent to a newsreel producer to promote the May 1963 opening of “Kuttner, Lueg, Polke, Richter,” a self-organized group show in an abandoned Düsseldorf storefront.

Five months later, Richter and Leug unveiled “Living with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism,” in a furniture showroom commandeered for the occasion. The two artists hung their paintings alongside furnishings positioned on plinths, which they occupied “not as artists, but as sculptures.” Richter himself lay on a sofa for the exhibit, and a papier-mâché effigy of then-president John F. Kennedy stood by a stairwell leading up to the show, concisely summarizing Germany’s existence under American hegemony.

Capitalist Realism was distinct from its American progenitor in both tone and focus, with the latter gravitating toward the commercial iconography of Hollywood and Madison Avenue and the former preferring actual, rather than manufactured, reality. “The message of American Pop Art was so powerful and so optimistic” Richter remembered. “It was not possible for us to produce the same optimism . . . or irony.”

-

Capitalist Realism versus Pop Art

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). Richter entered the Düsseldorf Art Academy that October. The school was at the center of contemporary art in West Germany, a vector for cutting-edge trends on the Continent. Among these were Art Informel, an analog to American Abstract Expressionism; the ZERO group, which explored light and movement through geometric abstraction; and Fluxus, an umbrella for an array of artists working in a performative life-as-art vernacular. One of Fluxus’s key members, Joseph Beuys, taught at the academy.

Most important, in Düsseldorf Richter met three fellow students, Blinky Palermo, Sigmar Polke, and Konrad Lueg, with the latter two becoming instrumental in creating the response to American Pop Art dubbed Capitalist Realism alongside Richter.

Playing off Socialist Realism’s name, Capitalist Realism wasn’t a movement so much as a series of collaborations among Lueg, Polke, Richter, and a fourth artist named Manfred Kuttner. It was a short-lived epiphenomenon meant as something of a joke, and Richter later expressed surprise at the renown it garnered, but considering his and Polke’s involvement, it’s easy to see why.

Capitalist Realism grew out of developments during the early 1960s in West Germany (which, like its eastern counterpart, was created out of Allied-occupied territory, albeit with a democratically elected government). While suffering hardships immediately after the war, West Germany benefited from America’s Marshall Plan, which galvanized the rapid rebuilding of industry and banking known as the Wirtschaftswunder (“economic miracle”) that transformed the country into a modern consumer society.

West Germany was also the Cold War’s front line, necessitating the presence tens of thousands of U.S. troops who brought the seductions of American popular culture (rock and roll, blue jeans, etc.) along with them. In the confrontation with the Soviets, this projection of soft power became just as important as military might.

Meanwhile, West Germans had yet to acknowledge their responsibility for enabling the rise of Hitler. Although the leaders of the Third Reich were put on trial at Nuremberg, most Nazis evaded the consequences of their actions, including members of the SS who directly participated in the Holocaust and other atrocities—among them Richter’s father-in-law, who, after a brief internment by the Russians, was allowed to return home and resume his gynecological practice despite his participation in the Nazi euthanasia program.

In a sense, West Germany wielded its economic success as a shield against this inconvenient past, preferring to focus on acquiring cars, TVs, appliances, and so on. The failure to reckon with Hitler’s legacy, along with Cold War geopolitics and American-style consumerism, became the targets of Capitalist Realism’s critique.

-

Photo-based paintings

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). Richter left the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1964 to fulfill ambitions galvanized by his excursion to Documenta five years earlier. Struck by the “sheer brazenness” of what he’d encountered there, he’d embarked on a series of compositions while still in Dresden that attempted to reconcile abstraction with representation. Inspired by Art Informel and Giorgio Morandi’s still lifes, the results were unsatisfactory according to Richter, and he destroyed most of them before turning to paintings tied to found photographs once he arrived in the West.

Among the first was Table (1962), in which Richter nearly erased the titular object (sourced from a high-end design magazine) in a swirl of scribbles. So began Richter’s persistent concealment of content as a way of revealing its larger meaning—a paradox that found its most notable expression in his blurring technique.

Although blurring became Richter’s trademark, he never considered it as such, saying that it was neither “the most important thing” nor the “identity tag for my pictures.” Nonetheless, it became synonymous with Richter’s work. He would imitate motion blur by dragging his brush horizontally across a still drying surface and soften his pictures to make them appear out of focus. Using both techniques, he evoked memory as something fleeting or faded with time.

Blurring also enabled him to achieve a “technological, smooth and perfect” appearance, which became more evident when Richter began to enlarge images with a projector. By the mid-1960s he began to copiously roll out paintings on a wide range of themes: bombers and fighters from World War II (Mustang Squadron, 1964); Cold War jet fighters (Phantom Interceptors, also 1964); slices of the Wirtschaftswunder good life (Motorboat, 1965); banal edifices (Administrative Building, 1964) and pornography, including a view of a young woman seated on the floor against a bookcase with her legs splayed (Student, 1967).

This period also saw Richter create his portraits of his Uncle Rudi and Aunt Marianne as well as Herr Heyde (1965), which he appropriated from a newspaper photo showing a former Nazi war criminal being hustled into court.

By 1966 Richter had begun to move beyond appropriations of found images and started to use his own photos as source material, beginning with Ema (Nude on a Staircase) (1966), an homage to Duchamp portraying Richter’s naked wife descending a flight of steps.

Ema arguably signaled a shift in Richter’s representational paintings, pushing them toward increasing levels of sublimity. From that point onward, he rifled through entire genres, generating, for example, flora studies (e.g., Orchid, 1997) and renderings of candles, which became some of his most recognizable images thanks to the appearance of one on the cover of Sonic Youth’s 1988 album, Daydream Nation.

Other works emerging in the wake of Ema were two unalloyed masterpieces, also portraits of family members: Betty (1988), which captures his daughter glancing back over her shoulder at a dark, empty space; and Reader (1994), featuring his third wife, Sabine Moritz, in profile, perusing a newspaper as a golden shaft of light illuminates the back of her neck as if this were a Renaissance annunciation scene.

-

Richter and abstraction

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). Whether gestural or geometric, abstraction had long occupied Richter’s attention alongside his image-based art, and the two often intersected. For instance, his “Color Charts,” which debuted the same year as Ema, appeared abstract but were in fact enlargements of hardware store paint chips conforming to Pop Art aesthetics. Equally poised between abstraction and representation were several earlier series, black-and-white renderings of curtain folds, sheets of corrugated metal, and grids given illusionistic depth with the artful deployment of shadows.

Another body of paintings consisted of impastoed views of cities from the air that sometimes devolved into overall squiggles of pigment. That they often resembled a bomber’s-eye view of an approach to a target was no accident.

Richter also combined pure abstraction with trompe l’oeil, making brushmarks, for instance, appear to float within three-dimensional settings. In Bunt auf Grau/Colors on Grey (1968), thick splatters of reds, browns, and blacks seem to hover over a gray field divided by sinuous lines in chiaroscuro, creating the odd impression of an upholstered surface. Another series, “Details,” begun in 1970, were based on close-up photos of thick brushstrokes in various combinations of pigment, turning paint into a realistic image of itself.

Richter’s blurring methodology became a subject itself with his most renowned abstractions, for which he added and subtracted multiple layers of paint by dragging squeegee-like implements loaded with different pigments across the face of a composition. Initially dating to the late 1970s, the process didn’t fully evolve until the 1990s. Much like Richter’s blurring or overpainting of photos, the squeegee technique was used to veil something underneath—in this case, fully realized paintings, both representational and not. The outcome could entail anything from lightly streaked still lifes to dense strata of paint peeking out through the gaps left by subsequent pulls of the squeegee.

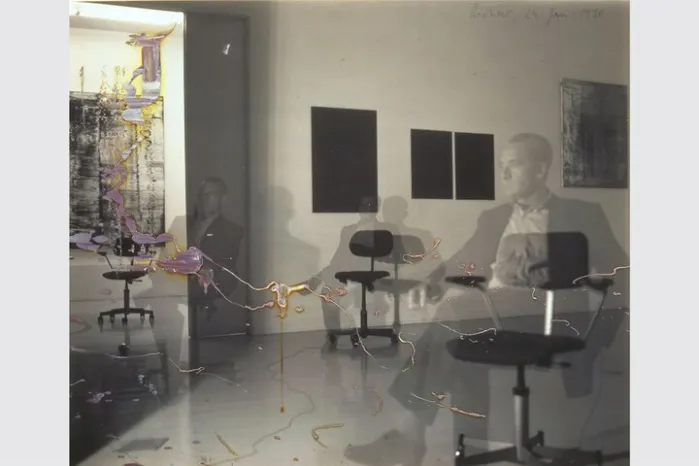

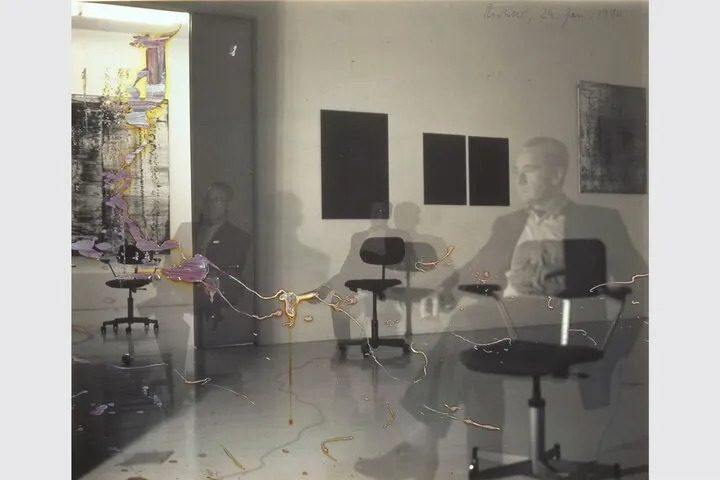

Beginning in the mid-1980s, Richter started painting on photographs he’d taken as an extension of his photo-based canvases, creating some 2,000 examples over time. Richter’s applied his inventory of abstract brushwork to these photos, many of which were almost entirely concealed by painterly bravura.

-

Atlas

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). While artists usually keep sketchbooks related to their work, Richter elevated the exercise into art with Atlas, a cache of photographs, clippings, drawings, and exhibition plans that he began to amass in the mid 1960s. Like its namesake, Atlas provided a map to the evolution of Richter’s practice over the years, starting out as an informal attempt to “accommodate everything . . . that was somewhere between art and garbage . . . that somehow seemed important to me” before turning into an archive-slash-installation of ephemera pasted into gridded arrangements on paper.

-

Sculpture

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). Sculpture has always been a key component of Richter’s efforts, with constructions made of glass being the most prominent. Consisting of freestanding plates of clear glass set on edge to form boxes or rows of parallel panes, or precariously propped together in configurations resembling a house of cards, they reflected and refracted the surrounding space as a physical embodiment of perception’s ever-shifting dynamics. Richter also used plate glass for large, wall-mounted reliefs reversed-painted with enamel in a single solid hue to cast reflections like vast colored mirrors.

The traditional medium of stained glass figured into a 2007 commission for a window on the south transept of the Cologne Cathedral. Covering 1,140 square feet, the project consisted of 11,500 glass squares in 72 colors, some randomly selected, and others chosen to chime with the church’s interior.

Another instrumental piece was Two Sculptures for a Room by Palermo (1971), a pair of busts of Richter and the Minimal abstractionist Blinky Palermo (his old Düsseldorf classmate) on tall pedestals facing each other with their eyes and mouths closed as if they were in a séance. Richter made it as his contribution to a mural installation by Palermo that covered the walls of a gallery in uniform panels of yellow ochre.

-

Richter and historical subject matter

Image Credit: Copyright © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0115). Richter returned again and again to the ruinous dialectic between violence and twisted ideation that had motivated the previously cited Uncle Rudi and Aunt Marianne. Another piece, September (2005), compressed the horrors of 9-11 into smoky wisps of squeegeed gray drifting over the immense trunks of the Twin Towers.

The most famous of Richter’s works, “October 18, 1977”(1988), is a 15-part cycle of grisailles meditating on the fate of the infamous German terrorist cell the Baader-Meinhof Gang, which in the 1970s had engaged in the kidnapping and murder of important figures from government and industry. Painted 11 years after the deaths of three members while in custody, it contrasted aspects of the group’s everyday existence (an apartment with record players, bookshelves, and other signifiers of the humdrum) with visual documentation of their deaths—which, while ruled suicides, likely came at the hands of the police. As if to put the fate of these radicals beyond understanding, Richter blurred the images almost beyond recognition.

Arguments have been made that Richter’s work exerts a kind of ethical force, though it’s fairer to say that it acknowledges the inadequacy of moral suasion in the face of monstrous depravities. For Germans like himself, this means the inescapable shadow of the Holocaust, which has always been the ghost in the machinery of Richter’s art. Some of the earliest sections of Atlas included photos of Auschwitz, and while Richter may have considered using them as the basis for paintings, he never did.

He eventually addressed the issue in a 2014 series, which he based on four indistinct photographs surreptitiously shot by an inmate at the Birkenau death camp from a door leading to the gas chambers. Haphazardly angled toward sky and landscape, the camera fugitively catches women and children being herded to their fates as piles of bodies are immolated nearby. Richter reprises the near illegibility of this eyewitness account in a group of large abstractions in which the imagery is buried under accumulations of repeatedly applied and scraped-off paint. When the Birkenau series debuted, Richter was accused of “canceling” the Holocaust, as if attempts to deny it hadn’t already happened. Indeed, these paintings are meant to confront the iniquity of such revisionism head-on.

Ultimately Richter’s significance stems from repurposing Theodor Adorno’s famed if often misinterpreted admonition that “after Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric.” Richter’s work suggests that he didn’t necessarily disagree, and even took Adorno at his word. In that sense, Richter pitted one form of barbarism against another as a necessary measure for uncovering the past with all its attendant pain.

Early life

Gerhard Richter was born the first child of Horst and Hildegard Richter in Dresden, Germany, a year before Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 (a sister, Gisela, was four years his junior). His father was a secondary school teacher and his mother a bookseller who played piano. In 1935 Horst moved the family to Reichenau, in present-day Poland, to accept a job there. At the outbreak of World War II, in 1939, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht, eventually becoming an Allied POW held captive until the war’s end. Released in 1946, he returned to his family, which in his absence had relocated to a village near the Czech border called Waltersdorf.

Horst had been compelled to join the Nazi Party to find work within the Third Reich’s educational system, and even then he’d had to settle for a post in a provincial backwater. This turned out be advantageous for Richter’s family, as Reichenau’s rural isolation insulated them from the prying eyes of the Gestapo and, early on at least, from the ravages of the war. Indeed, Richter recalled family life as “simple, orderly, structured—mother playing the piano and father earning money.”

But like the lives of all Germans at the time, Richter’s childhood was deformed by Hitler’s regime. Upon turning 10, he was required to join the Deutsche Jungvolk—the junior branch of the Hitler Youth—while the war exacted a personal cost on his family. Two of his uncles died at the front, including one, Rudi, who was immortalized in one of Richter’s blurred, monochromatic paintings from the mid-1960s (more to come on these as well). He likewise commemorated his aunt Marianne, who suffered from schizophrenia. Per Nazi policy, she was forcibly sterilized and committed to a psychiatric hospital. There she was starved to death as part of the Reich’s notorious T4 euthanasia program, which systematically murdered the disabled because they were deemed unworthy of life. She was dumped in a mass grave along with 8,000 other T4 victims.

More chillingly, Richter’s future father-in-law, Heinrich Eufinger, was an SS doctor assigned to the same hospital where Marianne was confined to administer sterilization procedures like the one performed on her—which he may have carried out, though that remains unproved. Eufinger appears in Richter’s Family at the Seaside (1964), smiling alongside his wife and children.

Richter was unaware of these details when he painted Marianne in 1965, as a portrait taken form a snapshot of himself as an infant sitting on her lap when she was 14. He found out only after the journalist Jürgen Schreiber uncovered the facts for his 2005 biography of Richter, Ein Maler aus Deutschland (A Painter from Germany). Still, when Richter was a boy, Marianne was treated as a cautionary figure, with his mother discouraging him from trouble by saying, “Don’t do that or you’ll end up like Aunt Marianne.”

Richter’s hometown of Dresden was devasted by Britain’s RAF in February 1945. While not present at the time, Richter was deeply affected by its destruction, and the bombing, too, would find its way into his work—most explicitly in 14. Feb. 45 (2002), an appropriated and retouched aerial reconnaissance photo of the ruined city of Cologne (bombed on the same day as Dresden) that testifies to how it still haunted him six decades later.

At the war’s end Richter’s family found themselves inside the Soviet occupation zone, which became Communist East Germany, a rump nation where one totalitarian regime was exchanged for another. Richter would remain there until his escape West in 1961.

Education

Thanks to his mother, Richter was exposed to monographs on Velázquez, Dürer, and the German Impressionist-cum-Expressionist, Lovis Corinth. He began drawing, and at age 15, in 1947, started to attend evening classes in painting while studying bookkeeping. A year later, he secured an apprenticeship at a company that produced banners for the East German government.

In 1950 Richter became a set painter for a theater, which eventually fired him for refusing to create a mural for its stairwell. Shortly thereafter, he applied to the Dresden Art Academy to study painting but was initially rejected. For the next eight months, he worked at a textile plant until finally gaining acceptance to the academy in 1951.

The Dresden Richter returned to was in ruins, with piles of rubble strewn along his way to class. The art academy, which had been damaged by Allied bombing but remained largely intact, emphasized Socialist Realism, the Soviet Union’s official style under Stalin. Luckily, Richter’s instructor, Heinz Lohmar, was relatively lenient about imposing the Socialist Realist line.

Richter kept in touch with developments in the West thanks to an aunt in West Germany who sent him books and periodicals on art and photography. Travel between the two Germanies was easier before the Berlin Wall was erected, and Richter took several trips to West Berlin, authorized by Lohmar, to experience the latest in Western film, theater, and art—which, along with Richter’s exposure to Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings at Dresden’s Pillnitz Castle museum, planted the seeds of his future work.

After graduating from the academy, Richter received several commissions as a mural painter. He could have easily continued down that path, but in 1959 he traveled West to Kassel for Documenta II, an international art exposition where he discovered Jackson Pollock, Jean Fautrier, and Lucio Fontana. It proved to be a pivotal moment, and in April 1961, shortly before the Berlin Wall went up, he and his first wife, Ema, defected.

Postwar West Germany

In 1963 Richter and Leug traveled to Paris to see an exhibition by the American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. They’d already been aware of Pop Art through art magazines, and while making their way around Paris’s galleries they introduced themselves as German Pop artists. The Capitalist Realism label was later coined by Richter in a letter sent to a newsreel producer to promote the May 1963 opening of “Kuttner, Lueg, Polke, Richter,” a self-organized group show in an abandoned Düsseldorf storefront.

Five months later, Richter and Leug unveiled “Living with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism,” in a furniture showroom commandeered for the occasion. The two artists hung their paintings alongside furnishings positioned on plinths, which they occupied “not as artists, but as sculptures.” Richter himself lay on a sofa for the exhibit, and a papier-mâché effigy of then-president John F. Kennedy stood by a stairwell leading up to the show, concisely summarizing Germany’s existence under American hegemony.

Capitalist Realism was distinct from its American progenitor in both tone and focus, with the latter gravitating toward the commercial iconography of Hollywood and Madison Avenue and the former preferring actual, rather than manufactured, reality. “The message of American Pop Art was so powerful and so optimistic” Richter remembered. “It was not possible for us to produce the same optimism . . . or irony.”

Capitalist Realism versus Pop Art

Richter entered the Düsseldorf Art Academy that October. The school was at the center of contemporary art in West Germany, a vector for cutting-edge trends on the Continent. Among these were Art Informel, an analog to American Abstract Expressionism; the ZERO group, which explored light and movement through geometric abstraction; and Fluxus, an umbrella for an array of artists working in a performative life-as-art vernacular. One of Fluxus’s key members, Joseph Beuys, taught at the academy.

Most important, in Düsseldorf Richter met three fellow students, Blinky Palermo, Sigmar Polke, and Konrad Lueg, with the latter two becoming instrumental in creating the response to American Pop Art dubbed Capitalist Realism alongside Richter.

Playing off Socialist Realism’s name, Capitalist Realism wasn’t a movement so much as a series of collaborations among Lueg, Polke, Richter, and a fourth artist named Manfred Kuttner. It was a short-lived epiphenomenon meant as something of a joke, and Richter later expressed surprise at the renown it garnered, but considering his and Polke’s involvement, it’s easy to see why.

Capitalist Realism grew out of developments during the early 1960s in West Germany (which, like its eastern counterpart, was created out of Allied-occupied territory, albeit with a democratically elected government). While suffering hardships immediately after the war, West Germany benefited from America’s Marshall Plan, which galvanized the rapid rebuilding of industry and banking known as the Wirtschaftswunder (“economic miracle”) that transformed the country into a modern consumer society.

West Germany was also the Cold War’s front line, necessitating the presence tens of thousands of U.S. troops who brought the seductions of American popular culture (rock and roll, blue jeans, etc.) along with them. In the confrontation with the Soviets, this projection of soft power became just as important as military might.

Meanwhile, West Germans had yet to acknowledge their responsibility for enabling the rise of Hitler. Although the leaders of the Third Reich were put on trial at Nuremberg, most Nazis evaded the consequences of their actions, including members of the SS who directly participated in the Holocaust and other atrocities—among them Richter’s father-in-law, who, after a brief internment by the Russians, was allowed to return home and resume his gynecological practice despite his participation in the Nazi euthanasia program.

In a sense, West Germany wielded its economic success as a shield against this inconvenient past, preferring to focus on acquiring cars, TVs, appliances, and so on. The failure to reckon with Hitler’s legacy, along with Cold War geopolitics and American-style consumerism, became the targets of Capitalist Realism’s critique.

Photo-based paintings

Richter left the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1964 to fulfill ambitions galvanized by his excursion to Documenta five years earlier. Struck by the “sheer brazenness” of what he’d encountered there, he’d embarked on a series of compositions while still in Dresden that attempted to reconcile abstraction with representation. Inspired by Art Informel and Giorgio Morandi’s still lifes, the results were unsatisfactory according to Richter, and he destroyed most of them before turning to paintings tied to found photographs once he arrived in the West.

Among the first was Table (1962), in which Richter nearly erased the titular object (sourced from a high-end design magazine) in a swirl of scribbles. So began Richter’s persistent concealment of content as a way of revealing its larger meaning—a paradox that found its most notable expression in his blurring technique.

Although blurring became Richter’s trademark, he never considered it as such, saying that it was neither “the most important thing” nor the “identity tag for my pictures.” Nonetheless, it became synonymous with Richter’s work. He would imitate motion blur by dragging his brush horizontally across a still drying surface and soften his pictures to make them appear out of focus. Using both techniques, he evoked memory as something fleeting or faded with time.

Blurring also enabled him to achieve a “technological, smooth and perfect” appearance, which became more evident when Richter began to enlarge images with a projector. By the mid-1960s he began to copiously roll out paintings on a wide range of themes: bombers and fighters from World War II (Mustang Squadron, 1964); Cold War jet fighters (Phantom Interceptors, also 1964); slices of the Wirtschaftswunder good life (Motorboat, 1965); banal edifices (Administrative Building, 1964) and pornography, including a view of a young woman seated on the floor against a bookcase with her legs splayed (Student, 1967).

This period also saw Richter create his portraits of his Uncle Rudi and Aunt Marianne as well as Herr Heyde (1965), which he appropriated from a newspaper photo showing a former Nazi war criminal being hustled into court.

By 1966 Richter had begun to move beyond appropriations of found images and started to use his own photos as source material, beginning with Ema (Nude on a Staircase) (1966), an homage to Duchamp portraying Richter’s naked wife descending a flight of steps.

Ema arguably signaled a shift in Richter’s representational paintings, pushing them toward increasing levels of sublimity. From that point onward, he rifled through entire genres, generating, for example, flora studies (e.g., Orchid, 1997) and renderings of candles, which became some of his most recognizable images thanks to the appearance of one on the cover of Sonic Youth’s 1988 album, Daydream Nation.

Other works emerging in the wake of Ema were two unalloyed masterpieces, also portraits of family members: Betty (1988), which captures his daughter glancing back over her shoulder at a dark, empty space; and Reader (1994), featuring his third wife, Sabine Moritz, in profile, perusing a newspaper as a golden shaft of light illuminates the back of her neck as if this were a Renaissance annunciation scene.

Richter and abstraction

Whether gestural or geometric, abstraction had long occupied Richter’s attention alongside his image-based art, and the two often intersected. For instance, his “Color Charts,” which debuted the same year as Ema, appeared abstract but were in fact enlargements of hardware store paint chips conforming to Pop Art aesthetics. Equally poised between abstraction and representation were several earlier series, black-and-white renderings of curtain folds, sheets of corrugated metal, and grids given illusionistic depth with the artful deployment of shadows.

Another body of paintings consisted of impastoed views of cities from the air that sometimes devolved into overall squiggles of pigment. That they often resembled a bomber’s-eye view of an approach to a target was no accident.

Richter also combined pure abstraction with trompe l’oeil, making brushmarks, for instance, appear to float within three-dimensional settings. In Bunt auf Grau/Colors on Grey (1968), thick splatters of reds, browns, and blacks seem to hover over a gray field divided by sinuous lines in chiaroscuro, creating the odd impression of an upholstered surface. Another series, “Details,” begun in 1970, were based on close-up photos of thick brushstrokes in various combinations of pigment, turning paint into a realistic image of itself.

Richter’s blurring methodology became a subject itself with his most renowned abstractions, for which he added and subtracted multiple layers of paint by dragging squeegee-like implements loaded with different pigments across the face of a composition. Initially dating to the late 1970s, the process didn’t fully evolve until the 1990s. Much like Richter’s blurring or overpainting of photos, the squeegee technique was used to veil something underneath—in this case, fully realized paintings, both representational and not. The outcome could entail anything from lightly streaked still lifes to dense strata of paint peeking out through the gaps left by subsequent pulls of the squeegee.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, Richter started painting on photographs he’d taken as an extension of his photo-based canvases, creating some 2,000 examples over time. Richter’s applied his inventory of abstract brushwork to these photos, many of which were almost entirely concealed by painterly bravura.

Atlas

While artists usually keep sketchbooks related to their work, Richter elevated the exercise into art with Atlas, a cache of photographs, clippings, drawings, and exhibition plans that he began to amass in the mid 1960s. Like its namesake, Atlas provided a map to the evolution of Richter’s practice over the years, starting out as an informal attempt to “accommodate everything . . . that was somewhere between art and garbage . . . that somehow seemed important to me” before turning into an archive-slash-installation of ephemera pasted into gridded arrangements on paper.

Sculpture

Sculpture has always been a key component of Richter’s efforts, with constructions made of glass being the most prominent. Consisting of freestanding plates of clear glass set on edge to form boxes or rows of parallel panes, or precariously propped together in configurations resembling a house of cards, they reflected and refracted the surrounding space as a physical embodiment of perception’s ever-shifting dynamics. Richter also used plate glass for large, wall-mounted reliefs reversed-painted with enamel in a single solid hue to cast reflections like vast colored mirrors.

The traditional medium of stained glass figured into a 2007 commission for a window on the south transept of the Cologne Cathedral. Covering 1,140 square feet, the project consisted of 11,500 glass squares in 72 colors, some randomly selected, and others chosen to chime with the church’s interior.

Another instrumental piece was Two Sculptures for a Room by Palermo (1971), a pair of busts of Richter and the Minimal abstractionist Blinky Palermo (his old Düsseldorf classmate) on tall pedestals facing each other with their eyes and mouths closed as if they were in a séance. Richter made it as his contribution to a mural installation by Palermo that covered the walls of a gallery in uniform panels of yellow ochre.

Richter and historical subject matter

Richter returned again and again to the ruinous dialectic between violence and twisted ideation that had motivated the previously cited Uncle Rudi and Aunt Marianne. Another piece, September (2005), compressed the horrors of 9-11 into smoky wisps of squeegeed gray drifting over the immense trunks of the Twin Towers.

The most famous of Richter’s works, “October 18, 1977”(1988), is a 15-part cycle of grisailles meditating on the fate of the infamous German terrorist cell the Baader-Meinhof Gang, which in the 1970s had engaged in the kidnapping and murder of important figures from government and industry. Painted 11 years after the deaths of three members while in custody, it contrasted aspects of the group’s everyday existence (an apartment with record players, bookshelves, and other signifiers of the humdrum) with visual documentation of their deaths—which, while ruled suicides, likely came at the hands of the police. As if to put the fate of these radicals beyond understanding, Richter blurred the images almost beyond recognition.

Arguments have been made that Richter’s work exerts a kind of ethical force, though it’s fairer to say that it acknowledges the inadequacy of moral suasion in the face of monstrous depravities. For Germans like himself, this means the inescapable shadow of the Holocaust, which has always been the ghost in the machinery of Richter’s art. Some of the earliest sections of Atlas included photos of Auschwitz, and while Richter may have considered using them as the basis for paintings, he never did.

He eventually addressed the issue in a 2014 series, which he based on four indistinct photographs surreptitiously shot by an inmate at the Birkenau death camp from a door leading to the gas chambers. Haphazardly angled toward sky and landscape, the camera fugitively catches women and children being herded to their fates as piles of bodies are immolated nearby. Richter reprises the near illegibility of this eyewitness account in a group of large abstractions in which the imagery is buried under accumulations of repeatedly applied and scraped-off paint. When the Birkenau series debuted, Richter was accused of “canceling” the Holocaust, as if attempts to deny it hadn’t already happened. Indeed, these paintings are meant to confront the iniquity of such revisionism head-on.

Ultimately Richter’s significance stems from repurposing Theodor Adorno’s famed if often misinterpreted admonition that “after Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric.” Richter’s work suggests that he didn’t necessarily disagree, and even took Adorno at his word. In that sense, Richter pitted one form of barbarism against another as a necessary measure for uncovering the past with all its attendant pain.

Tiffany & Co.’s Newest Bird on a Rock Jewelry Is Inspired by Wings in Flight

Kate Middleton Embraces Earthy Tones in Ralph Lauren, Barbour and More During Northern Ireland Trip With Prince William

Kalshi’s NFL Parlays Are Just a Tiny Slice of Total Trading Volume