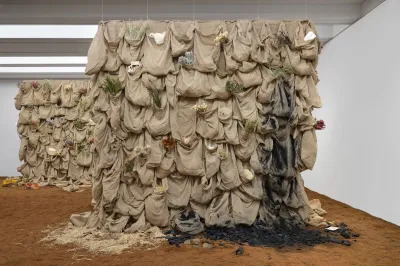

On a recent summer day in the Colorado resort town of Aspen, while some were hiking through the Rocky Mountains and enjoying the heat, the artist Solange Pessoa was indoors, strewing bones around the basement level of the Aspen Art Museum. She worked with purpose, careful not to disturb the layer of dirt already spread across the floor, moving among burlap sacks variously overflowing with with coffee beans, seeds with significance to Indigenous communities in Brazil, and brilliantly colored powders. Elsewhere on the basement floor, rose three tall towers formed by tiers of similar sacks; periodically ascended a stepladder to reach the uppermost tier of each tower.

The bags composing the towers were stuffed with papers printed with photographs of Spiral Jetty and Anastasi pottery, flower petals, feathers, dried peppers, sticks, and records by Brazilian musicians like Milton Nascimento, among other objects. And yet, Pessoa planned to somehow fill these sacks with even more materials.

“Seventy percent of their texts are missing,” she told me, speaking in Portuguese, with her gallerist Matthew Wood there to translate. “Usually, they’re overflowing from the bags.” Those texts would arrive in the coming days, ahead of her exhibition’s opening.

Pessoa created this piece in 1994 and exhibited it, albeit in a more modest form, in Belo Horizonte, the city where she has long been based. Over the last three decades, the artist has exhibited new iterations of the installation in locations ranging from Marfa, Texas, to Bregenz, Austria. The latest iteration, Bags – Aspen version (1994–2025), is the star of her current Aspen Art Museum show, one of her few solo museum exhibitions ever staged outside Brazil. She described Bags as “a wider anthropology of the Americas read through the tradition of the Earth.”

Bags is a work emblematic of Pessoa’s practice. It’s expansive and stately, and seeks to tether humanity back to the natural world. “I dislike the separation of culture and nature,” she said. “I have this imagination of an integrated philosophy, a natural philosophy, which incorporates culture as part of nature.”

Her practice draws no division between humankind and ecology. Bodily fluids are commonly enlisted for her sculptures, whose abstract forms tend to recall animals undergoing metamorphosis. Hair has also shown up in her work—most notably in Catedral (Cathedral, 1990–2015), a gigantic installation composed of a winding flow of leather and fabric with tresses stuck to it. (That work is owned by the Rubell Museum in Miami, where it has at points been accorded an airy gallery of its own.) These materials have often appeared alongside feathers, fruit, dirt, and more.

“She’s sensitive to anything that is living,” said Thomas D. Trummer, director of the Kunsthaus Bregenz, where he organized a Pessoa show in 2023 that included a version of Bags. “That might be plants, that might be seeds, that might be animals, that might be individuals.” For Pessoa, “everything is connected,” Trummer said.

In 2020, art historian Cecilia Fajardo-Hill wrote that Pessoa’s work had “only been getting the recognition it deserves in recent years, and mostly beyond the confines of Brazil”—something attributable to Pessoa’s decision to base herself not in an art hub like Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo but in the state of Minas Gerais. Then there’s the bitter reaction certain pieces have elicited in her home country: In 1995, when Pessoa made an installation called Jardim (Garden) that featured leather, hair, blood, and bovine eyes, the public responded with such negativity that one Brazilian newspaper called on her to explain its meaning. “These are strong works, but they were not made to scandalize,” she said at the time. She has still never appeared in an edition of the Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil’s top biennial.

Such a reception is hard to fathom now, while Pessoa is beginning to receive international fame. She appeared in the 2022 Venice Biennale, and she has gained representation with Mendes Wood DM, one of Brazil’s most prestigious galleries. (Blum, another blue-chip gallery, also represented her before announcing the end of its operations earlier this month.) Her Aspen Art Museum show coincides with another institutional solo exhibition, at Tramway in Glasgow. “Time has helped me grow,” Pessoa said.

It has also helped her grow her art, which is approaching monumental proportions. Deliria Deveras (2021–24), one of the installations in her Aspen Art Museum show, occupies an entire gallery and contains a mass of crystals punctuated by nuggets of silver. Those crystals together weigh 20 tons.

Deliria Deveras recalls a famed Robert Smithson installation composed of glass shards, and indeed, Pessoa cited Smithson and many Americans and Europeans working in the same paradigm as him—Land artists, Minimalists, Arte Povera sculptors—as being influential for her. Like those artists of the postwar era, Pessoa is fascinated by the notion that nature can be lured into clinical gallery spaces. But her work has an explicitly spiritual dimension that absent from the practices of her Western influences. “With absolute modesty, I feel like I’m trying to achieve something like the psychology of the relationship of man with an earthly God,” she said.

The crystals in Deliria Deveras were mined in the Brazilian city of Ferros, where Pessoa was born in 1961. The mining industry was all around her—Minas Gerais has a long history of mineral extraction—and so, naturally, wound its way into her art. “There’s this psychological aspect to mining,” she said, referring to the act of digging beneath the surface. She called herself a minero, punning the Portuguese word for both “miner” and a person who comes from Minas Gerais.

Pessoa grew up on a farm in the remote town of Dores do Indaiá and was raised in the vicinity of many churches filled with many sculptures of saints (which are sometimes adorned with human hair, just as her sculpture Catedral is). Though Pessoa does not herself identify as a Catholic, she noted that she has a “spiritual intuition” and said she drew inspiration from the rich tradition of Baroque art in Brazil’s churches. Alongside Land artists and Minimalists, she also named Aleijadinho, an 18th-century sculptor whose work can be found in Minas Gerais’s churches, as one of her primary inspirations. Pointing to all the sacks in Bags, she said, “Certainly, these are all Baroque—the folding, the verticality, the excess, the emotional intensity.”

She attended art school during the ’80s and during the ’90s began making sculptures that adhered to no dominant trend in Brazil: circles of bones, masses of vegetable fiber that hung to the wall and extended onto the floor, knots of hay that dangled from rafters like a giant’s braids.

“She’s a real outlier in her generation,” said Matthew Wood, Pessoa’s dealer. “This wasn’t what people were doing, and certainly not what people valued.”

Some artists began taking note. Pessoa became friendly with Tunga, whose sculptures had emboldened her to use hair in her own art; she even became a member of the Galpão Embra collective alongside him. Through Galpão Embra, she also showed her work alongside artists such as Ione de Freitas and Nuno Ramos.

Even after being pilloried in the press for Jardim, the 1995 installation that featured bovine eyes, she showed no desire to conform to trends. She exhibited her work outdoors, in places far removed from museums and galleries, and she continued to make sculptures that were likely to disturb viewers. Lesmalongas – Desterros (1998–2002), a piece divided into five “situations” (four of which were staged on her family’s farm), featured sculptures made from plastic and a combination of lard and dirt. Some were worn by performers who screamed and wailed, as though Pessoa’s creations were hurting them or forcing them to become animal-like. Pessoa admitted that her work does offer “sensorial perturbation,” and said, “I like when works take me out of my comfort zone.”

But for Pessoa, pieces like Lesmalongas accomplished more than shocking their viewers—they established a new relationship between people and their surroundings. “Blurring the [boundary] between human and nonhuman is very important to her,” said Claude Adjil, a curator at large at the Aspen Art Museum and the organizer of Pessoa’s show there.

In the past couple decades, Pessoa has continued producing art musing on that very theme, though her work no longer seems designed to unsettle in the way that it once did. Years ago, she began making drawings that resemble animals that do not actually exist (“insects emerge from her mind and are not entomologically correct,” art historian Cecilia Fajardo-Hill once wrote); she has recently begun exhibiting them with greater frequently, in venues such as the 2022 Venice Biennale. And she has begun working in bronze, which is longer-lasting than many of the organic substances she used during the ’90s.

She’s also enlisted soapstone, a material once used for commemorative statues and fountains, for sculptures such as NIHIL NOVI SUB SOLE (2019–21), which appeared outside the Arsenale during the 2022 Biennale and is now being exhibited on the roof of the Aspen Art Museum. Into this soft stone, Pessoa has carved leaf-like forms that collect rainwater. That rain, in turn, further alters the surfaces of her sculptures, which were already mottled from exposure to the elements.

Pessoa is keenly aware that her sculptures might not last forever—and she has even embraced that quality of her art. “I feel the necessity of ephemerality, but on the other hand, I also feel the necessity of eternalization,” she said. “These contradictory philosophies are inseparable.”

Khaled Sabsabi, Michael Dagostino Reinstated for Venice Biennale After Creative Australia U-Turn

Liz Collins Finds Transcendence Through Labor-Intensive Fiber Art

These Cruise Ships Are Using Lavish, Multi-Story Suites to Appeal to their Highest-End Seafarers

Tom Brady Debuts $650,000 Signature Jacob & Co. Watch at E1 Monaco Grand Prix

Apple’s upcoming iPhone lineup is the most exciting we’ve seen in years

WNBA Players Say ‘Pay Us’ as Commish Offers Sunny CBA Outlook