It’s fitting that a major survey of the maze-like abstractions of Portuguese French artist Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–92) is taking place in Venice, a city whose labyrinthine streets unexpectedly burst into piazzas. In these paintings, patchwork planes of vibrant, tile-like squares intersect and stretch, while scaffoldings of interwoven lines float in a dimension of their own. They reveal hidden openings and crevices, and they deepen with meaning the longer one stares at them.

These artworks are having a moment following a period of obscurity. They were the main attractions of a large, traveling exhibition held in Marseille and Dijon between 2022 and 2023, and they featured in the Centre Pompidou’s 2021 “Women in Abstraction” exhibition, which helped put Vieira da Silva back on the general public’s radar. That momentum is likely to only grow from here: her Venice survey, at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection through September 15, heads next to the Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain.

Unlike most female artists of her generation, Vieira da Silva was a star in her day. She was included in the historic 1943 “Exhibition by 31 Women” at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in New York, and by the mid-1950s, she had shown twice at the Venice Biennale and brought her work to cities as far and wide as Rio de Janeiro and Stockholm. She and her husband, the Hungarian-Jewish artist Arpad Szenes, formed a celebrity couple, mingling with fellow avant-garde creators in Paris, where the couple met, studied, and lived during the late 1920s and ’30s and after World War II. (Vieira da Silva had more acclaim and more success than Szenes, a rarity for her day.) Georges Braque personally encouraged Vieira da Silva to keep working, and Fernand Léger taught her while she was a student at the Académie Moderne in Paris in 1929. She also learned sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, who was then assisted by Germaine Richier and Alberto Giacometti.

Vieira da Silva is now the subject of new fascination because, she both “doesn’t fit neatly into any sort of category, but then addresses broader themes that very much speak to our present moment,” said Guggenheim curator Flavia Frigeri, who was recently appointed curatorial and collections director at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Specifically, Frigeri pointed to the artist’s World War II–era depictions of human tragedy. In these figurative works, people of unknown origin or politics are swept into chaotic, violent upheaval, which they can neither control nor escape. Their bodies are rendered in simplified, often angular and flattened strokes, merging with the Cubist landscapes that surround them. One such memorable painting is called The Disaster (1942).

These works are high among those that “explain why we’re rediscovering her, or why I felt it was important to rediscover her,” said Frigeri.

The artist’s practice has also sparked the curiosity of a younger generation unfamiliar with her work, in part because it seems to evade traditional classification. “We couldn’t find any direct link between the artist and any art movement,” said Naïs Lefrancois, curator at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, who co-organized the 2022 Vieira da Silva exhibition. The artist has previously been associated by some with the Art Informel movement of the 1940s and ’50s, but Lefrancois said the linkage doesn’t quite hold up. “She insisted on not being part of a group, and she wanted to maintain her freedom. She didn’t want to be classified and categorized,” Lefrancois explained.

That very elusive quality was also what intrigued Frigeri about Vieira da Silva’s paintings when she first saw them at Tate Modern, where she previously worked. “I couldn’t quite place her,” Frigeri said.

Véronique Jaeger, whose great-grandmother was the first to give Vieira da Silva a solo show, and whose eponymous Jeanne Bucher Jaeger gallery represented the artist her entire life, said the world was now ready for artists like this one. “We are constantly in situations where we can take one road or another, and all of these perspectives, which are present in her paintings—all these labyrinths, all these mazes, where space doesn’t stop progressing, elongating, stretching—that was pretty much her vision,” said Jaeger, who now serves as president and director of the family’s gallery. “There’s always an opening somewhere. Even in paintings where we have the impression it’s closed, there’s an exit.”

Vieira da Silva herself exuded an openness to a range of artistic styles. She was interested in Futurism, Cubism, medieval frescoes, and the geometry of Hispano-Arabic azulejo tiles, which can be found all over Lisbon, where she was born and raised by her mother and grandparents. She traveled around Europe with her family to look at art, and was supported in her creative ambitions. Because her grandfather ran a newspaper, she was able to keep abreast of cultural happenings, feeding her interest in modernism.

The very spaces she painted were also porous—they appear to break down, meld, and grow. “My latest paintings often feature shapes that other people see as houses, but which for me are interiors with doors and windows, not exactly rooms but rather entrances,” she once said. “For me the door is a very important element. For a long time now, I’ve had the feeling that I’m standing in front of a closed door, with essential things happening on the other side that I can neither know nor see. And it’s death that will open the door for me.”

But it took some time to develop those shifting spaces. Her Peggy Guggenheim Collection show goes heavy on works made during the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, with attention given to the influence of her early sculpture and human anatomical studies, offered here as a starting point toward abstraction for Vieira da Silva, and a means of expressing her interest in both real and imagined space. The artist studied anatomy as part of her fine arts program at the Escola de Belas Artes in Lisbon in the 1920s and was known to carry bags of bones home to sketch. “She goes from the body’s interior, to space,” said Jaeger, adding that the artist painted very slowly. “She was a bit like a tightrope walker, walking along a thread while experimenting and exploring space as she slowly painted. There was a lot of silence. She spoke little, but she lived everything around her intensely.”

An only child born to an affluent family in Lisbon and tutored at home, Vieira da Silva spent hours alone, sifting through the family library, which included books on both the art of the past and her present. “I took refuge in the world of colors, in the world of sounds. I believe that all these influences merged into one single entity, within myself,” she once said. Once, while she was still a child, she got lost inside a maze, in what proved to be an unforgettable experience. Maze-like forms would later appear in her paintings, as a metaphor for life and an allusion to how we experience the passage of time.

After her drawing and painting studies at the Escola de Belas Artes, in 1928, Vieira da Silva moved to Paris at the age of 19 to continue training at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. There, she met Szenes, whom she married two years later and stayed with until his death in 1985. In the French capital, Vieira da Silva blossomed as an artist alongside Szenes, who strongly encouraged her. Ultimately, her exposure to works by Picasso, Matisse, Bonnard, and Cézanne led her to form her own artistic language in the ensuing years.

A pivotal moment in Vieira da Silva’s early artistic experimentation came in 1931, soon after her arrival in France. In the old port of Marseille, she was impressed by a transporter bridge with suspended cables that appeared light, despite its massive size. This aspect “influenced her perception of space as a fluid and untethered form.” She pushed further in the following years and, in 1935, made a piece titled La Chambre a carreaux [The Tiled Room]. Largely inspired by music, this interior, warped checkerboard perspective of colors was an early breakthrough .

In 1940, with World War II roiling Europe, Vieira da Silva and Szenes relocated for a year to Rio de Janeiro, where she began working in a figural mode, painting expressions of her terror at global events. The couple ultimately returned to Paris in 1947. The works made during her postwar period draw inspiration from urban landscapes and architectural interiors and exteriors, and show her moving further toward abstraction.

From the looks of the Venice show, Vieira da Silva tried her hand at a variety of formal experiments between the ’30s and the ’50s, and then appeared to fall into a more repetitive mode in the years afterward. But based on what’s here, it’s also striking to consider whether her work is more influential than most realize. Jaeger said that Louise Bourgeois described Vieira da Silva as an inspiration, and one could compare the latter artist’s work to paintings by Julie Mehretu, who likewise abstracts architectural spaces.

Such comparisons could not have hurt what Jaeger describes as strong market interest in works by Vieira da Silva, whose paintings can sell for up to $900,000, according to the dealer. And, as Lefrancois pointed out, there is mounting fascination with women artists of Vieira da Silva’s generation.

The Guggenheim show certainly makes Vieira da Silva’s art feel singular and thrilling. Of particular note is her 1952 painting Terrasse Ensoleillée [Sunny Terrace]. Made while she was back in Paris, this golden canvas features a net-like arrangement of yellow squares. The pattern looks like a bit like dappled sunlight, but it also implies the breakdown of order. As with her practice more broadly, this painting suggests another world—one where the eye must learn to see in new ways.

Italian Museums Are Now Offering Dog-Sitting Services to Boost Visitor Numbers

In the Early 20th Century, Jean Cocteau’s Queer Art Was Notably Cocksure

The Largest Piece of Mars on Earth Just Sold for a Record $5.3 Million

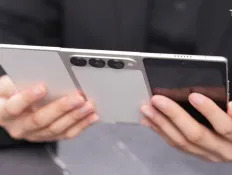

World’s first G-shaped trifold smartphone is official

Novel Finish to MLB All-Star Game Arrives Too Late to Save TV Ratings